This is Faith in Play #99: Sidekicks, for February 2026.

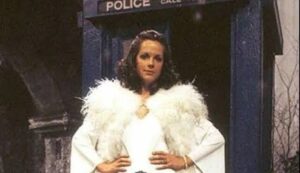

Mary Tamm, who played Romana (Romana I, for fans) when (now) Sir Tom Baker was Doctor Who, commented in a documentary special that her job was to say “What is it, Doctor?” in as many different ways as she could manage. There is some truth to this; if we look at Burt Ward’s Robin in the early Adam West Batman series, his job was not much different, nor indeed was the original Watson to the original Holmes. It might be notable that when Peter Davison took over the iconic British science fiction role, his companions either had significant skills–mathematician Adric (Matthew Waterhouse) and scientist Nyssa (Sarah Sutton)–or were significant to the plot (Janet Fielding’s Tegan and Mark Strickson’s Turlough), so perhaps the comment sparked something for the writers. However, there is a genuine aspect of sidekicks that they are there to provide support for the main character.

My first reaction was that this doesn’t really happen in role playing games, because the player characters are all main characters in the story, and usually their non-player companions are their equals in the adventures. However, from the beginning there have been subordinate characters–henchmen, hirelings, retainers–usually run by the referee as supporting characters for the players. Yet there is a degree to which such characters are a bit less human.

I noticed this when I was collaborating with Eric R. Ashley on Multiverser novels: to me, companions of viewpoint characters, the primary versers, didn’t really have a separate story; their story was that they were accompanying the verser, effectively the player character. For Eric, these were people who had a right to their own stories, pursuing skills, friendships, companions of their own, and honestly it threw me, because I wasn’t writing about them except as they related to their primaries. Yet he was right–the sidekicks need to be people, need to say more than “What is it, Doctor?” Their relationships to each other and to other people matter. We needed to provide three-dimensional lives for these people who traveled alongside our main characters. They needed to be people.

I’m reminded of stories in which a main character suddenly says to his companion, “I didn’t know you could do that,” or some similar expression of surprise. On some level that should happen, that our sidekicks, companions, henchmen, hirelings, retainers, associates, should have interests and abilities of which the main character, the player character, is unaware. As a referee or a writer, you need to flesh out these people, make them real, or they become two-dimensional, flat, genuinely boring.

Make your secondary characters interesting, surprising. It makes them more real, and so makes the story and the world more real.

Previous article: Apocalypse.

Next article: Sacrifice.