This is RPG-ology #73: Sense, for December 2023.

Our thanks to Regis Pannier and the team at the Places to Go, People to Be French edition for locating a copy of this and a number of other lost Game Ideas Unlimited articles. This was originally Game Ideas Unlimited: Sense, and is reposted here with minor editing [bracketed].

I can smell mold spores.

At least, that’s what I think I smell. It’s an odd odor that tickles my nose when I’m around molds–in the swamps of Salem County or the onion bin at home. You see, I’m allergic to mold spores, and I’ve learned to recognize that when that smell reaches my nose I really should move away, because my breathing is going to start shutting down fairly soon. So I’ve been trained to notice it. My wife thinks it’s all a bit crazy. She can tell one variety of rose from another by smell, and is constantly irritated that I can’t even tell one perfume from another (but all cause me to wheeze), but she doesn’t smell whatever it is that tips me to the presence of those spores. I suspect it’s a sort of survival response I’ve developed. I’m sensitive to the smell of something that’s going to endanger me. I can always smell it when it’s around, and there’s nothing else that smells like it. Rather, there’s almost nothing else that smells like it.

Mold spores smell like patchouli.

That’s right. The oil often used in men’s fragrances gives me exactly the same olfactory sensation as mold spores. My wife doesn’t smell it that way; she sort of likes patchouli. Every time I smell it, I think the mold spores count is up and I’d better go get some medicine before I stop breathing. We don’t smell the same thing when smelling the same thing.

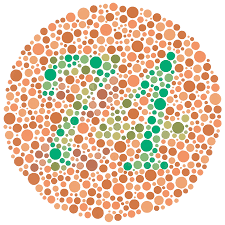

In the same vein, I have long wondered whether we all see the same thing. After all, how could we really know?

There are young children who need glasses while in elementary school, but they never think to suggest to their parents or teachers that they can’t see the board well. They assume that everyone else sees what they see; if it looks blurry to them, that must be what it really looks like. In much the same way, we assume that all of us hear the same sounds, see the same colors, smell the same odors, and taste the same flavors. But it is not always true. We know that even normal sense varies in unexpected ways among humans, even without impairment or handicap. Gustation–taste–for example does not at all follow the anticipated patterns. You probably think that there’s something of a bell curve, in which a few people have extraordinary ability and a few terrible ability, and most people are in the middle. In fact, it seems that gustational abilities clump at the ends–a cluster of people with exceptional taste buds, a very few people with average ability, and the majority of us grouped at the bottom. Wine tasters really do taste better (as any dragon will tell you).

So why do we assume that everything always seems the same to all of the characters in the game–and particularly when they aren’t all human?

In fairness, not all games do this. Star Frontiers made a point of describing the sensory abilities of its four major races, which included (as I recall) that dralasites saw only black and white images, vrusks had trouble hearing lower frequencies, and yazirians could see well in dim light but had very sensitive eyes which required dark goggles in bright light. But even when there are obvious differences, these are not carried through to their logical conclusions. I have elsewhere suggested that if a character can see heat this would have significant effects on his perceptions of color in objects; it is even possible that objects would change color, at least a bit, if they were different temperatures–and hot objects should appear brighter than cold ones, even in fairly bright light.

This is a major challenge. It is already difficult to present a world to your players the way their characters experience it. To add that the characters don’t all perceive it the same way can be a major complication for the referee. Although I played a dralasite, I was regularly given information about what color things were, and even thought about the use of color by others. But there are ways you can use this to give the experience new dimensions.

In the dwarf quarter of one of my cities there are bakeries famed for their dwarf pastries. As soon as I had created these, I realized that they could not produce Napoleons and eclairs or even donuts; they had to produce something that would seem so alien to my human players that they would immediately realize these were not made for their palates. So the garlic cream pastry was born, a smooth garlic paste in a flaky crust. Alongside sat clove cakes, their strong flavor a delight to the locals. The human player characters never tasted these; but the elves tried them, and decided that perhaps dwarfs knew something about food.

I played in one world in which there were seven moons; one of these was called the Death Moon, and we were told that it was called that because it reflected no light and so was invisible. As I was becoming familiar with this world, it suddenly occurred to me to ask how we knew it was there if we couldn’t see it. The referee’s answer was that it was visible to infravision; that meant that it was a warm object. But my character had infravision, and so to him the so-called Death Moon was never invisible and threatening, but warm in its appearance as compared to the cold light of the other six moons. What to men was a cold, hidden threat blotting out the stars as it passed unseen through the sky was to my people a warm beacon–an entirely different cultural response to the same object, because of a different perceptive ability.

This of course is just color in the world; but will all characters like the same food? Will they even be able to eat the same food? Could a water source be potable for some but not for others? Can some see things clearly which others cannot see at all? Are there sounds that one character can hear which the others cannot, no matter how hard they listen?

Take it to another level, the next logical step: do the characters know that they don’t see, hear, smell, taste the same thing? Why should they? In another world, a human was impressed by the fact that her werewolf allies could always spot vampires and ghouls and other undead creatures, even when they looked quite normal to her. It took a long time for her to realize that it was not the look but the smell of the thing that revealed it to them. If the elf sees or hears something, would he not just assume that his companions do so as well? If the dralasite can recognize the taste of arsenic in the food, is he going to realize that his companions aren’t aware of it? And if arsenic is not poisonous to him, would he think to warn them?

In some stories, only children can see fairies; in others, it’s angels, ghosts, or invisible rabbits, and only some, or only one, can see them. What really distinguishes the senses of your character races, or even individual characters? There’s a lot of possibility there.

Next week, something different.

Previous article: Multiple Staging.

Next article: Senseless.