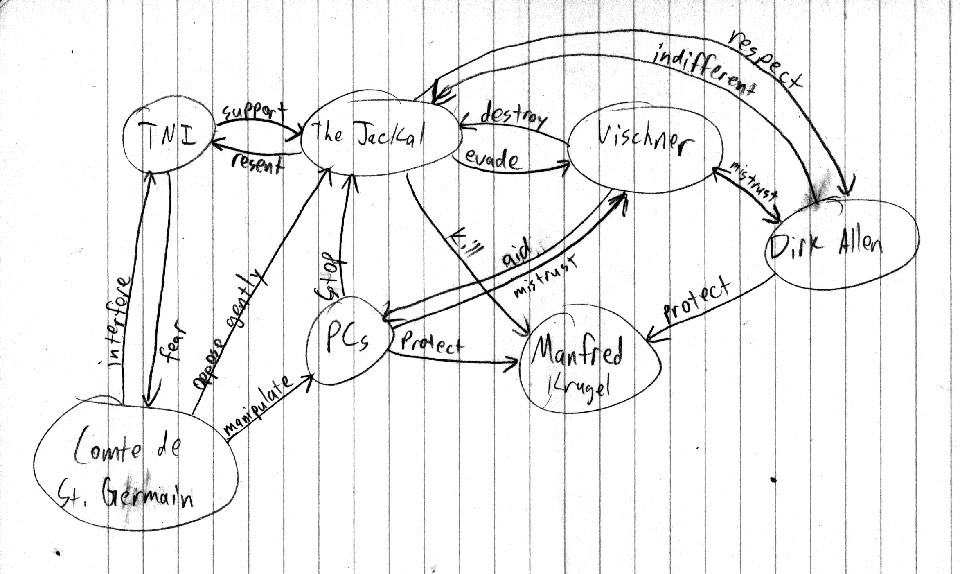

I was in a conversation recently about how Game Masters manage factions—how do you track their activities and relationships? I use a technique of mind mapping. If you’ve never heard this term, a mind map is a drawing that abstracts the relationships between people, organizations, nations, etc into a spatial diagram. It can look similar to a flowchart, but it doesn’t necessarily progress to an end point. Here’s a sample of a map I used for planning a long-ago Unknown Armies campaign:

This is a fairly simple web describing the efforts of “The Jackal” to assassinate the politician Manfred Krugel, an act intended to secure his place as the Godwalker of The Assassin. The primary force in opposition to The Jackal is an individual named Vischner. The map was built around these two—The Jackal and Vischner—with the Player Characters and Krugel occupying a subordinate but still central position. This was my initial organizational chart, representing what I anticipated to be the overall structure of the campaign.

Although it is fairly simplistic, having a reference for how each NPC or group feels about all the others helps for when the PCs do something unexpected. If they capture a New Inquisition agent and decide to start asking questions about the Comte de St. Germain, then I have only to look at my chart to know that the agent will react with (justified) fear. If they ask the same questions of Vischner, he’ll just be confused. There are no arrows between St. Germain and Vischner, indicating that they do not interact. Of course, depending on the nature of the questions, Vischner’s curiosity might be piqued, and I’d add an arrow to represent it.

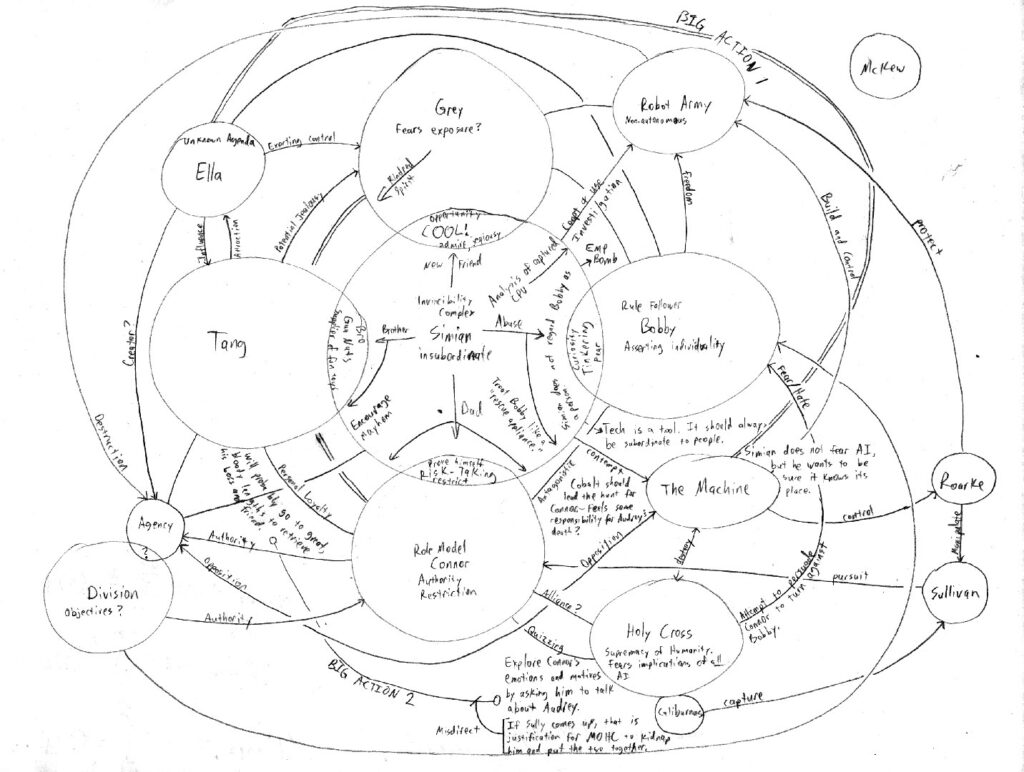

Mind maps can, of course, be much more elaborate. In the Circuit Breakers campaign, which I have written about previously, I occasionally used them in planning individual sessions. As the game grew more complex, these maps likewise became more detailed. Here’s the map I prepared for Simian’s spotlight episode:

Simian himself occupies the large central circle, with each of the other Protagonists arrayed around him and overlapping his circle. The internal notes and arrows represent how Simian relates to each of the others. Simian’s player went AWOL after the first session, requiring me to play him as a Game Master’s Character. Since this episode was focused on him, and since Primetime Adventures is so unpredictable, I gave myself plenty of detail to guide my play. Having this guide about Simian’s attitude toward each of the other Protagonists, as well as all the other factions involved, allowed me to relax into the role and keep my attention on facilitating a good story.

One thing that is difficult to do with a mind map, as much as I like them, is to show how a faction’s plans will progress over time. If you have a dynamic campaign world, with multiple time-tables to keep track of, you’ll need a different solution, although a map like these might still be useful. My own habit is to keep my factions in stasis—they maintain the status quo until such time as a destabilizing force (that is, the PCs) appear. In those circumstances, the mind map is usually all I need.

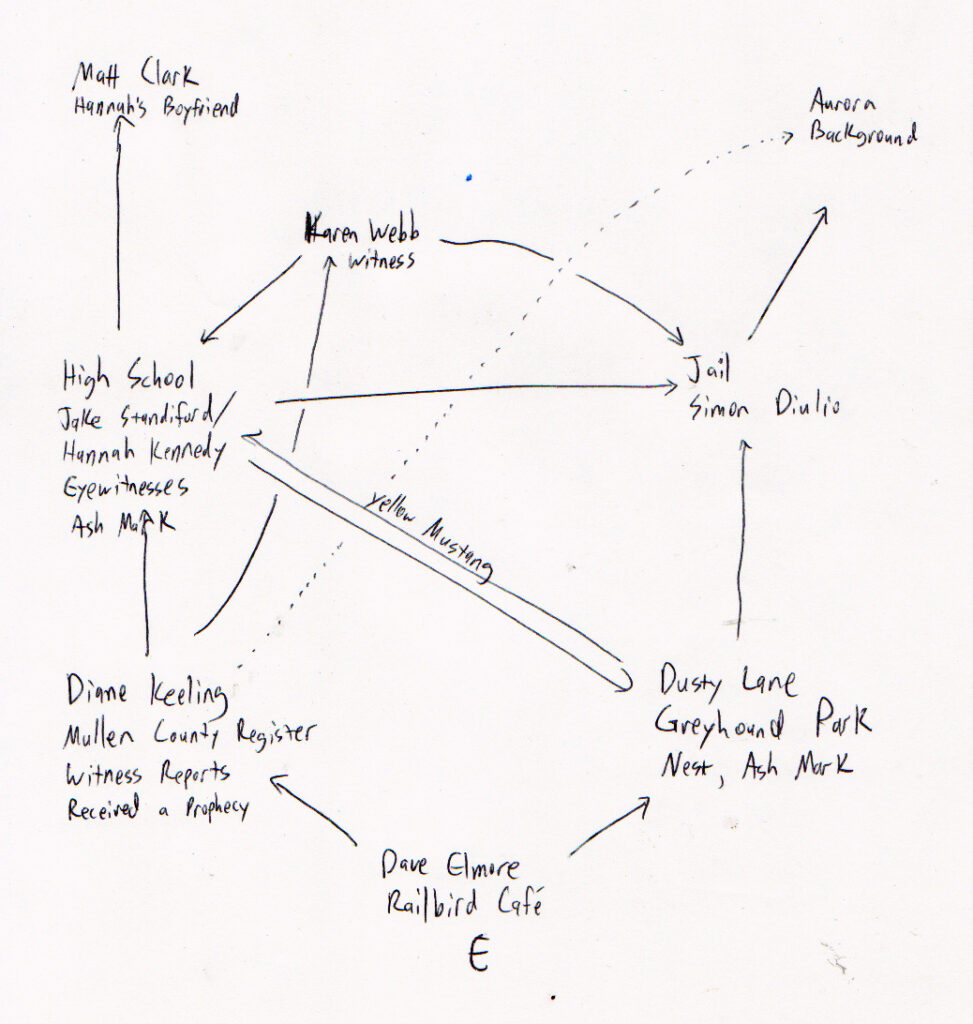

I also use mind maps to plan sessions, particularly mysteries, where I need to be sure there are enough connections between encounters that the PCs will be able to uncover the entire story. This one describes an encounter with the Mothman in yet another Unknown Armies campaign. The map was less about governing my play than it was about planning. I needed to ensure that there were at least two ways for the players to come across each of the people who had important information. The map is actually unfinished—apparently I didn’t update it after I’d discovered that there were insufficient connections to Karen Webb. My notes indicate that I gave Dusty some information about Karen—he’s the local sheriff and had investigated her report of a break-in at the high school.

This was a fun game to plan and to run. Mysteries can be delicate, given the typical play group’s ability to entirely miss the point and go haring off after a clue that never even existed (don’t put deliberate red herrings into mystery games—the PCs will manufacture their own). In such a scenario, it’s important to keep things simple—there were only five crucial people involved here, and the PCs didn’t actually even need to meet all of them (although the climax was more compelling with more of the story revealed).

If the map had grown any more complex, it would have indicated a plan likely to unravel. The two leaf nodes (an element that has incoming connections but no outgoing ones) are problematic, as they indicate potential for the story to stall. Aurora, at least, was actually a sort of ‘wild card’ clue holder. She was also investigating the town and could point the PCs at any witness they’d missed, but it would have been pointless to then draw arrows from her to everywhere. Matt was a little bit of trouble, as an encounter with him didn’t provide any additional actionable information, so I attached him to a couple of independent events I could use to prompt the PCs back into action if they dead-ended there.

I have picked up quite a few tools over the years for helping me plan sessions. Mind maps are one of my favorites—they make a lot of sense to me, and they prevent me from falling into the trap of trying to anticipate the PCs’ every action. When the map starts to look too tree-like, with possible events forking into infinity, then I know I need to rethink the design. By refocusing on relationships and attitudes instead of events, I keep the scenario flexible enough to adapt to the unexpected.