This is Faith in Play #6: True Religion, for May 2018.

In the earliest versions of Dungeons & Dragons™, the original role playing game from which all others (including those electronic games that call themselves “RPGs”) are descended, there was a rules section known as alignment. Many players did not understand it; many gamers did not use it; it was often badly abused. However, I think it was one of the best and most important parts of the game, and I often defended and explained it.

I am going to make the perhaps rather absurd claim that I am a recognized authority on the subject of alignment in original Advanced Dungeons & Dragons™. I know, that’s ridiculous. However, I am also going to prove it. When Gary Gygax was promoting his Lejendary Journeys role playing game, he placed on his web site exactly two links to pages related to Dungeons & Dragons™ One was to my Alignment Quiz, which had already been coded into an automated version by a Cal Tech computer student and translated into German. The other was my page on choosing character alignment in my Dungeons & Dragons™ character creation web site. He apparently believed I had a solid understanding of the issues.

So big deal. I’m an expert in a game mechanic concept that isn’t even used by most of the few people who still play that game. However, even if you don’t use it, don’t play that game, I think alignment is important to understand, because ultimately the character alignment was the real religious beliefs of the characters in the game world. Sure, there were scores of gods—even the controversial volume Deities & Demigods did not contain them all, and when I was compiling them I had to dig through several other rule books to find them. But what god you listed as your character’s religion was of only incidental value in the issue of what you really believed. Alignment was what really mattered.

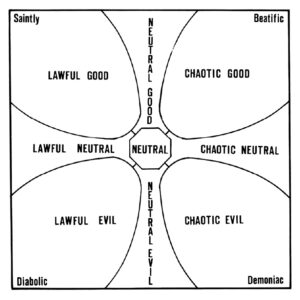

Among those many pages lost when Gaming Outpost crashed was a series about alignment, which proves to be a fascinating bit of game theory even if you never play the game and have no use for alignment. As I recall, the first installment in that miniseries was entitled Belief, and it addressed this issue. I often find myself telling people that what you really believe will control how you act—if you have not seen my Parable of the Boiler it explains this quite well, but let me instead recount comments by atheist Penn Jillette (of Penn & Teller). He spoke highly of someone who politely confronted him with the claims of the gospel. Jillette’s comment was, if you honestly believe that people who do not accept this message are going to hell, and you don’t tell them, you must really hate them. He’s right of course. Most of us don’t really believe what we say we believe; what we really believe is expressed in our actions. Alignment was a system which in essence gave two sets of opposing principles, labeled good and evil and law and chaos, and let you declare where your character stood in relation to them; it then connected adherence to those principles to in-game consequences. It made you declare what your character really believed, and then have him act like he really believed it.

In reality, we get to label ourselves anything we want, whether Christian or socialist or feminist, and act however we wish without reference to what we claim to be. In Gone with the Wind, the old slave woman heads off to do what the mistress of the mansion asks even while she’s shouting over her shoulder that she’s not a slave anymore—”I’s free.” More recently in Sherlock, Mrs. Hudson offers tea but repeatedly qualifies, “I’m not your housekeeper, I’m your landlady.” What is our real belief, about ourselves, about our world? Is it what we say, or what we do? What we do arises from our motivation, and our motivation is controlled by what we actually believe. If you want to know what someone really believes, watch what he really does. He might want to think otherwise; he might even believe that a different set of beliefs is a better set. When the rubber hits the road, though, what he does is completely controlled by what he actually believes.

So as you play your characters, think about what they actually believe, and how that impacts what they do, what they would really do if they believed what they said they believed—as we saw in Javan’s Feast a few months ago. See if you can make your character’s actions consistent with what you think he believes.

Meanwhile, what is true of the character is the more true of you. Examine yourself, and ask whether you act as if you really believe what you think you believe. If not, you have some reevaluation to do somewhere.

I will return to the alignment issue—there are at least seven more articles on the subject waiting to be written—but I will spread it out over the next few years so it doesn’t dominate the column here. Again, if there are particular issues you would like to see covered in this series, let me know.

Previous article: Fear.

Next article: Coincidence.