This is RPG-ology #10: Labyrinths, for September 2018.

In game terms, a labyrinth is a geometric puzzle, a system of passable and impassible spaces solved by the discovery of a consecutive path of passable spaces connecting some number of points, commonly the entrance and the exit. A maze, usually, refers to a type of labyrinth for which there is a unique solution, only one path that connects two points; a labyrinth might instead have many solutions, or no solution. The distinction is significant in several ways; they are related puzzles, but both the ways in which they are created and the techniques for solving them are different.

Engraved and designed by Toni Pecoraro 2007. http://www.tonipecoraro.it/labyrinth28.html CC BY 3.0

Labyrinths can occur naturally, when geologic forces crack rocks in seemingly random patterns. Even mazes can be naturally occurring—if a tunnel system was carved by water which has since mostly evaporated or drained away, it commonly carves one exit point, and then the current follows that path and ignores the others. Mazes are more commonly created by intelligent action, although sometimes an intelligence will create a labyrinth for any of several reasons.

Labyrinthine road patterns sometimes develop from the process of acretion, as new residents add new housing and thus new streets attached to old ones. Suburban developments are often labyrinthine by design so that residents familiar with the roads can exit in any of several directions but others will not consider the connected roads a viable short cut between two points outside the development.

The Minotaur was kept in a labyrinth because a maze would have been too easy to solve.

A maze in two dimensions is easier to solve from above than from within; the eye can trace patterns and look for the connecting path, spotting and avoiding dead ends early. Still, from within a two-dimensional maze you are guaranteed to find the way through if you pick one wall and follow it. This will take you into many dead ends, but it will take you out ultimately. A labyrinth with more than one solution cannot necessarily be solved this way, as there is a high probability that you will be caught in a loop.

Three-dimensional mazes are considerably more difficult to solve, because we are not generally accustomed to considering them three-dimensionally. These are most easily created as multi-level constructions with stairways, ramps, or chutes and ladders connecting them in specific points, often connecting some levels but not accessing intervening levels.

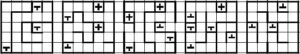

Five level three-dimensional maze, top level to the left, crossbars mark ladders, with markers for up and down. Entrances are on the middle level, center of left and right sides.

One mistake often made in maze design is designing inward only—that is, many mazes are easily solved by working backwards, the tricks and turns and deceptive paths all designed to mislead the one coming in from the front. This is not as much of a problem in a role playing game maze, because these can often be placed in locations in which the characters will initially approach them from one side. On the other hand, the designer can take advantage of this by creating the maze backwards, such that characters will easily find their way in but will be confronted by the confusion on the way out. However, many tabletop gamers become very good at mapping, so the scenario designer might need some particularly complicated tricks to stymie his players.

Fortunately, fantasy and science fiction give us such tricks. In Dr. Who: The Horns of Nimon, the space in which the Nimon lived was a giant logic circuit, the walls switches which seemingly randomly switched from “A” to “B” positions making it impossible to have an accurate map created from passing through it. I have recommended using teleport points, in either fantasy or science fiction settings, by which any character crossing a specific spot on the map in a specific direction is moved to a specific other spot on the map not necessarily facing the same direction, but is not moved back on the return journey, passing the arrival point unaware that it was there. There are many ways to use this—creating recursive occlusion, as in Dr. Who: Castrovalva, a section of the map in which there are many entries, but only one exit, all the other exits delivering you to the entry point on the opposite side of the isolated area; creating maze-like labyrinths in which the characters are moved to parallel paths but the occupants know how to use their teleport points to get where they want to be; creating duplicate rooms in which characters who enter one room always leave from the other. I have used all of these techniques, and have had players trying to resolve their situation for several play sessions.

I have also confused players by using maps with repeating patterns, causing them to believe they had returned to a place they had already been when they were instead in a different place exactly like it. Nothing is quite the same as watching a player attempt to erase and correct a map that was already right.

Previous article: Three Doors.

Next article: Scared.