Back when I started gaming, almost twenty years ago, there was practically no material on how to have a good game—so I had to learn the hard way. All of the tips, tricks, and advice in this article come from years of GMing badly and gradually getting better. Watching other GMs that you like and practicing a lot are some of the best ways to improve your game.

Good judgement comes from experience. Experience comes from bad judgement.

Please don’t use this article as an excuse to dump on your fellow gamers by saying “Look, it says here that you’re a bad gamer!” Likewise, don’t feel that if you don’t do all of these things that you’re not a good gamer, and realize that this is not a complete list of good gaming qualities. Just use this article to improve your own gaming techniques.

Good Gaming

There are lots of ingredients that go into a good game. Good people, good people skills, and good ideas work together to create a good gaming experience. Arguably the most important person in a game is the Game Master. In the gaming circles I’ve been in, at least, players will pursue a good GM to run their games, but I’ve rarely seen a GM pursue a good player—there are normally too many players per GM as it is.

A good GM can achieve his goal of a good game by thinking quickly during a game and by preparing for the game ahead of time.

During the Game

A good GM must fulfill six important roles: director, writer, referee, host, actor, and tactician.

GM as Director

In theatre, the director is the person that controls the flow of the story. When I was in the theatre, I worked with directors with a number of different styles. Some were dictators, micromanaging every detail of the entire play into their vision of how it should be. Some were coaches, urging the participants to do their best. Some were hands-off, and just selected talented people to work with, and told them to go find their own direction.

As director, a good GM must make some of the same choices. Does he keep the game on track by gentle prodding or an iron fist? Does he prepare beforehand or completely wing it? Does he just give input when the players feel stuck or lost, or does he practically hand them a script to follow?

Lights! Camera!

As director, a good GM has to set the mood for the game. A room dimly lit by a dozen or so candles, a spy movie soundtrack playing in the background, or a few fake jungle vines on the table and chairs will all give feelings that are appropriate to different genres. But mood props, while enhancing the atmosphere, should not be the only measure taken.

Mood of any kind is truly set by our actions and words. Genre speaking patterns (“Prithee my lord” versus “Ya, whaddya want” versus “Please input response”), accents, physical gestures, and phraseology (“Some knights on horses come up to you,” versus “You hear the galloping hooves and you see and smell the dust they kick up as the horsemen approach— there appear to be four horses, each with a rider, but you cant make out the details from this distance”) all set the mood for a game.

Action!

Action!

As director, a good GM also has to keep the action rolling. Pausing a game to wait on a slow-counting player to finish adding up the damage from a 12d6 roll is a waste of time. Waiting for a player to declare a combat action while the player keeps asking what’s going on even though it’s already been explained three times is a bad move. Allow the villains to make poor decisions as well if it will speed the game up. Indecision: a disease commonly found in sheep. To solve some of these slow-downs in the game, a GM can delegate—have players with a head for numbers do all the die totaling for the slow players. Or, if the GM wants to figure it up early, he can pre-roll lots of common die rolls and mark them off as they’re used. I’ve even heard of percentile charts and index cards as methods to reduce counting time.

If the problem is one of players not paying attention during combat, talk to them about it. If they still don’t get it together, you can award fewer experience points for roleplaying, make them lose in-game time for their character to assess the situation whenever they ask what’s going on, assign a penalty to the characters actions for daydreaming, or simply skip over their turn.

Focus

As director, a good GM also needs to keep the players in character. Games are meant to be fun, but if the game’s mood is serious, it is not the time for the players to exchange puns, or to talk about their car problems, or to do homework. If it were another game being played, like basketball or charades, the focus would be on the action, not on the sidelines.

Role-playing games should, when appropriate, be treated the same way. Some appropriate times for seriousness might be when the heroic knights approach the evil wizard’s castle, when the doomsday device begins to grind gears and give off sparks, or when the elevator begins to flood with river water. There are plenty of times for levity, as well, however. When the GM gets so excited that he stutters the master villain’s death threat, when the team brick beats up a Shriner just to get a fez, or when a hero’s wimpy alter ego kills a villain with a lucky punch and so gains a bigger rep than the hero, are all great times for a good laugh. And there are plenty of times that a single character might logically lighten a dark mood with a well-timed quip or prank. When it is time, however, for immersion into the roles, a phone call for the GM or someone opening a crinkly bag of chips can be most distracting.

There are plenty of ways for a GM to ensure that players stay in character. A barrage of thrown dice, a 25¢ penalty box, deducted experience points, etc. all work well enough, but the surest way to keep the game on track is to GM for players who are already inclined to do it. This is obviously not easy, but once a GM finds good players, he needs to hang on to them.

As for getting the players into their characters at the beginning of a game, I’ve seen Get in Character drills that worked well. At the start of each session, the GM asks a player a question about his character—who’s the first person you ever killed, who was your favorite teacher and why, when were you the most content, etc. and after answering, that player asks another player a different question. This helps set the mood for gaming, and also teaches all present something about the characters that they might not have known.

Organization

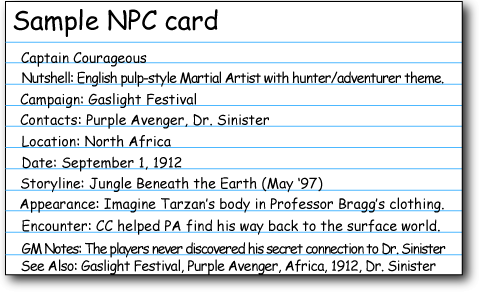

As director, a good GM is also organized. Whether in his head or on paper, a good GM knows whats going on in his world—who, where, when, why, and how. Keeping an NPC cardfile helps to keep track of this relevant info.

As director, a good GM is also organized. Whether in his head or on paper, a good GM knows whats going on in his world—who, where, when, why, and how. Keeping an NPC cardfile helps to keep track of this relevant info.

It might be hard to remember the name of the guide who escorted the heroes across the city two years ago, or to remember how many yahrens are in a centon, or what day of the week it was when the heroes left town. But by keeping index cards (or computerized records) on the major and minor events and people in the game world, the GM can always have those nearly-forgotten memories on hand.

The Fourth Wall

In theatre and film, the fourth wall is the wall between the performers and the audience. Breaking the fourth wall is any action that reminds the audience that whatever they’re seeing is not real. Ferris Bueller looking at the camera and explaining to the audience how to fake a generic illness, Tigger speaking with the narrator, and Bugs Bunny stepping outside of the film frame are examples of breaking the fourth wall.

Games can break the fourth wall, as well. As director, the GM can choose to do this.

A character (not the character’s player) could get a phone call at the game. “Okay, its phase 12—hang on, the phone’s for you, Jake.

“Hello?”

“Caped Wonder, I know what you did, and I’ll go to the press if you don’t confess.”

A character could get mail (either regular or e-mail). A postcard addressed to a character can really surprise a player.

Example: My superhero team had an assignment in another state. As it happened, I had to drive through that state a few days later. I sent a postcard from a character to the rest of the group.

Director Summary

As director, a good GM gets and keeps his players attention. The players focus on the game, and the game focuses on the plot. Players stay in character, and the game moves along briskly.

Have a tip related to setting the scene, keeping your players focused, or staying organized? Share them in the comments!

Stay tuned next week for Experience Talks: GM as Writer!

This article was originally published in The Way, the Truth, & the Dice, issue 1 in Spring 1999. Due to its length, the Editor has elected to serialize it over the course of the next few weeks.

Action!

Action!