A Three Act Opening:

A Story Within a Story

By Michael Garcia

Originally written February 2022

More on George Lucas’ and Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)? Has Mike seen any other movies?, you ask. The film is admittedly one of my favorites, and, as I continue to discover, it seems to be the gift that keeps on giving. It’s also fun to rewatch, so I never mind going back to it.

Before continuing, it’s important to note what every experienced DM already knows–that designing RPG adventures is very different from writing movies (and novels). DMs simply do not have control over the main characters as screenwriters (and novelists) do. Yet, there are several tips and tricks that we can borrow from Hollywood.

In several articles, I’ve already mentioned tips that we can take from Raiders. In Single Session Design Tips, I mention how you can use quick transitions to fast-forward through long journeys, much as the movie shows Indy moving from country to country with a moving red line. Also, while noting how Johnn Four’s Five-Room Dungeon idea ensures that an adventure has the basic ingredients of a good time, I note how the opening of Raiders seems to mirror the 5RD design. In yet another part of the article, I note how the beginning of any adventure can start with excitement, much as Raiders begins with those now-famous 12 minutes. In Customizing Player Characters, I note how Indiana Jones has a fear of snakes, which humanizes him. In Designing the Ruins of Ur-Ammon I note how an exciting opening, like that in Raiders, doesn’t need to relate much to the main plot (the opening might simply show us more about the hero or the villain).

Fan-based Art (creator unclear, found on Pintrest)

A few days ago, I stumbled upon a 2020 video by Carter Thallon for Insider (a news website, I guess?). It was entitled How Raiders of the Lost Ark Reveals Everything that You Need to Know about Indiana Jones in 10 Minutes. As Raiders is one of my favorites, I had to click the link, though I didn’t expect to see much more than I already knew. I was pleasantly surprised. The narrator’s main point is that Lawrence Kasdan, the screenwriter of Raiders, used the same three-act structure for the opening that writers usually use for an entire Hollywood film. This explains why that opening is so rich, as well as why it’s so satisfying all by itself. To underscore his point, the narrator briefly contrasts the opening of Raiders with those of The Mummy (1999) and Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001), both of which heavily drew inspiration from Raiders (to be clear, in The Mummy, the first six-and-a-half minutes form a prologue about ancient times; the video’s narrator is referring to the next four-minute sequence, wherein we meet the main character). In each of those two action-packed openings, you learn very little about the main character, and there is little sense of story. In contrast, after the opening of Raiders, you know a lot about Indiana Jones, and you feel as if you’ve been through an entire adventure with him already. This ‘story within a story’ also tells us what to expect in the rest of the movie. For example, we know that the tone of Raiders is serious, yet there are bits of comedy skillfully woven in. We also see that Indy will fail and lose, but he is doggedly persistent. Most of all, we see that Indy is a brave man of action.

These observations sent me back to watch the opening of Raiders once again (twist my arm), this time with a very critical eye… and wondering whether we might learn even more for use in our RPGs. So I watched it again, scene by scene, and I agree with the Insider video’s narrator. Kasdan does largely follow a three-act structure, skillfully packing a ton of information into a very short period. But how? With such tight time constraints, what types of information does he include? How does he write so efficiently? There is more to be learned here, I thought. The following article provides five things: (1) my observations of the opening of Raiders, (2) a very brief overview of the three-act structure, (3) how the opening of Raiders follows this structure, (4) a few thoughts on openings in RPGs, and (5) what lessons and tips we might borrow from Lawrence Kasdan in creating our own RPG openings. If you are still interested, read on.

Breakdown of the Opening of Raiders

First, let’s closely examine the opening of Raiders for ourselves. Why? Can’t we skip right to lessons learned? Most casual fans know something of the opening–that Indy avoids several traps, grabs a gold idol, runs from a giant boulder, and escapes from natives. What more do we really need? It’s easy for fans to miss just how much is packed in that opening. When I teach my high school students to examine historical cartoons and documents, my first instruction is to look closely at everything before you start trying to apply your knowledge. We want to make sure that we notice everything that the artist or filmmaker is trying to show us. So here follows my breakdown, without making any role-playing connections. My breakdown likely differs from some others on the internet because I ignore camera angles and other cinematographic tricks, as they have little meaning in RPGs. I timed the following sections as well as I could, but I imagine that different video clocks might show slightly different time stamps. Mine should be close enough for practical use. In a few places below, I included names or nationalities that you don’t learn in the film. They are not necessary for the viewer, but they make this article clearer.

0:0 – 0:30

Indy is the first figure that we see. He wears rugged and worn clothes, fitting for the environment. He takes a few seconds to study the landscape, suggesting that he knows where he is going. The party is in a beautiful, isolated, mountainous area. Several hirelings come into view, carrying all manner of gear, indicating that their quest is not a simple one ( In the film, I count two Spanish Peruvians and about five native porters). Indy is out in front, carrying very little, suggesting that he is a leader. At least one hireling, a Spanish Peruvian named Satipo, looks tired, and his shirt is stained with sweat, suggesting that the trip has been arduous to this point. Another hireling, a Spanish Peruvian named Barranca, looking annoyed, yells in a foreign language for the porters to hurry. His use of an unfamiliar tongue confirms that the party is in a distant land. The music is soft, subdued, and mysterious.

0:30 – 1:30

Indy leads the party through a thick, tropical jungle. The many sounds of the jungle are now evident. Indy still leads the way. The party is then viewed from behind trees, as if others were watching its movement. We see for a split second that the native porters lead two beasts of burden, suggesting again that their quest requires more gear than they can carry. Rotting leaves cover the jungle floor, and vines drape between the trees. The foliage becomes too thick to bring a mule any further (I think it’s a mule). The music remains subdued. A native porter then discovers an ancient statue (probably related to part of the temple complex that they are seeking) and runs off, terrified, as bats fly out of the statue’s mouth. It’s unlikely that he is that afraid of the bats, so the statue must hint at some terrible danger–perhaps the people that built the temple or the temple itself. In any case, Indy keeps his cool and studies the statue, again indicating his knowledge of arcana. Though we don’t see it on film, all five of the native porters must have run off because we don’t see them afterwards.

1:30 – 1:50

The two remaining hirelings, Satipo and Barranca, look nervous, looking behind them for some unseen danger in the jungle. Why are they afraid? What’s out there? The group moves forward, crossing a stream, delving deeper into dangerous territory.

1:50 – 2:20

The two hirelings spot a dart in a nearby tree. Indy casually investigates, indicating again that he is knowledgeable about such things. By touch, he notices something on the dart. He appears unmoved by the discovery and casts it aside, whereupon the two hirelings rush over to retrieve the dart, showing their anxiety. By taste, Satipo confirms that the dart is poisoned, making it clear for us that the unseen danger is deadly. Then we learn of its nature–native Hovitos. Satipo suggests that the Hovitos are following them, thereby increasing tension, and Barranca makes the Hovitos seem even more deadly by saying “If they knew we were here, we’d be dead already”. So, we know that the group is in Hovito territory. Again, the two look about nervously. They are in shadow as they speak.

2:20 – 2:51

The three continue to push forward. The lighting here is eerie, with rays of sunlight coming through the trees. The sounds of the jungle become more prominent. A caption then gives us some context, namely the location and the year. At a river or pool, Indy is out in front again, as if checking their location. He is shrouded in shadow, and still we do not see his face, keeping him mysterious. He consults some old parchment fragments, showing us that he is knowledgeable enough to understand them and suggesting that he must have expended considerable time and expense to collect the fragments. Satipo looks on curiously, as Indy studies the fragments.

2:51 – 3:24

Barranca, with thoughts of betrayal clearly on his face, then draws his revolver quietly, behind Indy’s back. Indy detects the faint sound, showing us that he is far more alert than we imagined (he does not display the tunnel vision that we might expect from an academic). Without warning, Indy turns, produces a bullwhip, and skillfully lashes the traitor’s hand, disarming him. Barranca runs off, and for the first time we see Indy’s face, firm and resolute. He is still calm and collected, undeterred. He calmly puts away the whip and moves on, as Satipo looks at him in awe.

3:24 – 3:58

Indy and Satipo then move up a steep rise to the half-buried, gloomy, entrance of the ruined temple. Indy begins filling a sack with sand, suggesting that he knows something of what lies inside. In casual conversation, he also mentions that his very talented competitor, Forrestal, vanished there. In just three lines, we get a hint of Indy’s past–presumably racing about the globe on other adventures like the current one. Satipo now tries to convince Indy to turn back, saying that no one has come out of the temple alive. With just a sentence, he explains some of the native porters’ fears and provides all that we need about the dangers of the place. By ignoring his warnings, Indy displays his courage.

3:58 – 5:05

With Satipo carrying a torch, the two enter a dark tunnel of stone, shrouded in cobwebs. We then see Satipo warn Indy that he has a couple of tarantulas on his back, which Indy calmly brushes off with his whip. Satipo then finds his own back covered with them (and admirably remains still as one runs across his neck!). Indy assists Satipo, calmly brushing off the spiders.

5:05 – 5:31

We then come to a light-triggered spike trap, which Indy recognizes and disarms, again highlighting his knowledge. Still impaled on the spikes is the corpse of his late competitor, Forrestal. Satipo, in many ways a surrogate for the audience members, screams in fear at the sight, but Indy remains calm. We now have satisfying closure about the disappearance of Indy’s long-time competitor, though we only learned about him two minutes earlier in a mere two sentences.

5:31 – 5:59

Next we see Indy using his whip to cross a deep pit, which seems to be about 10’ wide. This again shows us Indy’s skill with the whip, and we note that he uses it in an unorthodox way. He makes the crossing look easy, but when Satipo attempts it, he almost falls into the pit, showing us how most of us would fare in that situation. Moreover, Indy shows his agility and character by saving Satipo’s life. Satipo’s little misstep raises the tension a little higher. Also, that pit is now an obstacle that they’ll need to cross on their way out, and if they’re returning in a hurry, that pit might be a problem.

5:59 – 6:50

The two then move to the edge of the large idol chamber, where a grotesque golden idol sits atop a stone platform. The overgrown room is extremely interesting, with what seem to be several stone seats near the walls, grotesque faces carved into the walls, tangled vines, roots, and moss growing in many spots, and sunlight falling on the golden statue. Satipo, again a surrogate for audience members, sees no danger and almost walks into certain death, while Indy senses the danger, prevents Satipo from getting killed, and then finds a dart trap, triggered by a hidden pressure-plate (that’s three times that Indy has helped or saved his hireling). In the midst of this serious adventure, we get a hint of comedy when Satipo agrees not to enter the chamber (“If you insist, señor”). Not only is it funny, but it also underscores Satipo’s understandable fear.

6:50 – 7:11

Having seen the look of the pressure plate seconds earlier, we now see that the floor could be covered with such pressure plates. As Indy walks forward, we also see that the walls are covered with carved stone faces, the same type that just fired a dart. Any one of those faces (or every one of them) might fire a dart. Indy almost loses his balance, and Satipo gasps. These tiny details combine to make Indy’s simple crossing of the room seem exciting. Realize that every one of those potentially live traps now lies behind Indy, making a quick exit dangerous. Tension continues to rise.

7:11 – 7:53

Indy is now before the idol. He produces the sack of sand and tries to guess the idol’s weight (a lot harder than it seems, for it is unlikely to be solid, and even if it were, its irregular shape would make calculations difficult). As Indy pours out sand, the camera focuses on the idol, which seems menacing. Satipo famously fidgets in anticipation. Finally, we have the moment of truth, when Indy quickly makes the switch, replacing the idol with the sack of sand.

7:53 – 8:25

For a few precious seconds, the switch seems successful, and Indy smiles and turns. Then the center of the platform sinks, Indy realizes his mistake (the first that we see), Satipo’s face falls, and all Hell breaks loose. The pace picks up dramatically, releasing all the pent up tension. The walls of the chamber collapse outward and stones rain down from the ceiling. Indy breaks into a run, charging through a cloud of flying darts. We’re not sure what dangers remain once the pair leave that chamber, but the characters flee in a hurry. Satipo swings back across the pit, but the whip comes undone, and he falls unceremoniously on the far side. What should normally have been a simple task–getting the whip from Satipo–becomes complicated. First, Satipo asks Indy to throw him the idol, bringing trust issues into play. Tension begins to build again. Not a second later, a heavy stone door begins to close, creating urgency. Indy was already betrayed by one hireling, but he has little choice and no time to think. He throws the idol to Satipo, at which Satipo betrays him and leaves him to die. Meanwhile, the door is still closing, the tension increasing.

8:25 – 8:54

Indy immediately tries to jump the chasm. He cannot clear the pit, but he does catch hold of the edge. Racing against time, he lunges for a root, hoping to pull himself up. He succeeds, but then it comes loose (tension rises some more). He finally manages to pull himself up and to roll under the stone door just in time (simultaneously grabbing his whip).

8:54 – 9:47

Indy then turns to find Satipo impaled on another spike trap, giving us satisfaction at seeing the man punished for his treachery (of just forty seconds earlier). Indy picks up the idol but has no time to celebrate, for a giant boulder then releases to seal Indy in the temple. Indy runs for his life (coincidentally, Harrison Ford was also running in earnest, for the boulder prop weighed 300 pounds, and he was indeed running in front of it; even funnier, they did several takes, but they used the one in which Ford slipped and fell). Just feet in front of the boulder, Indy runs through a tangle of cobwebs and hurls himself out of the temple entrance. He tumbles down the dirt slope, only to find himself face to face with a host of angry-looking Hovitos, who level their weapons at him. The treacherous Barranca is also there, dead from the poison of more than a dozen darts (more gratification). The natives let the corpse fall unceremoniously at Indy’s feet.

9:47 – 10:41

We now meet the French archeologist named Belloq, Indy’s arch-rival. His opening two lines tell us all that we need to know–that he has repeatedly taken Indy’s prizes, and that he does not give up. Indy removes his revolver and considers fighting, but the Hovitos wordlessly threaten to kill him. In just four back-and-forth lines, we learn that Belloq is shady, that he speaks the Hovito language (indicating that he is as well-educated and worldly as Indy), and that he has a sense of humor.

10:41 – 12:44

When Belloq turns away and the Hovitos kneel, Indy runs for it, showing that he doesn’t give up easily either. At Belloq’s signal, the warriors give chase. Indy hurtles through the jungle, races across an open field, and heads towards a floatplane, waiting in a nearby river. We get a few seconds of comedy as we see the natives swarm over the crest of a hill behind Indy. The comedy continues when Indy’s pilot, who just caught a fish, wrestles for two seconds with whether to throw away the fish and the rod, as Indy screams for him to start the plane. Indy then races through the trees lining the river, swings on a vine, plunges into the river, and swims toward the moving plane, all while the Hovitos shower him with poison darts and arrows. We get one last thrill when Indy finds the pilot’s pet snake in his seat. We get one last glimpse into Indy’s personality, when he announces with anger and fear that he hates snakes. We get one last laugh when the pilot laughingly tells Indy to show some backbone.

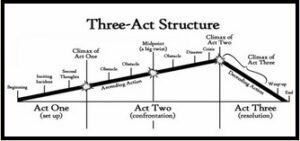

Overview of the Three-Act Structure

Writers like to debate the history of the three-act structure, with some claiming that it’s a very modern construct, while others claim that it goes back to Aristotle. Suffice to say that elements of the structure were around since Aristotle, but it took roughly twenty-five centuries for the structure to become common. In 1979, an American screenwriter named Syd Field made it wildly popular with his book, Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, now considered to be the ‘bible’ of modern screenwriting. In 2005, screenwriter Blake Snyder broke the three-act structure into fifteen pieces (or beats), creating a template that Hollywood screenwriters have used almost exclusively since then. While Blake’s precisely-timed breakdown is too formulaic for many, Field’s three-act structure is a bit looser and more malleable. You can find countless websites that explain the three-act structure or Blake’s fifteen beats in detail, but the following is my crude summary and amalgam of both.

Syd Field identified Act 1 as the Setup, which constitutes roughly 25% of the story. Act 1 often begins with a hook, but in general, the author introduces the protagonist and the setting in which he lives. The author then uses an inciting incident to set the story in motion by introducing some problem that faces the protagonist (this could be a villain, a rival, or just an undesirable circumstance). The protagonist’s attempt to deal with this problem eventually leads to an event called the first plot point, just before the end of Act 1. This event forever changes the protagonist and raises the dramatic question that the end of the story will reveal (like “Will Indy obtain the Lost Ark?”).

Syd Field identified Act 2 as the Confrontation, which constitutes roughly 50% of the story. This starts with the protagonist reacting to the first plot point. In general, the protagonist repeatedly fails to solve the problem and finds his situation increasingly worse. Tension increasingly rises. Despite the setbacks, the protagonist usually undergoes character development during this act, meaning that he obtains information about the forces facing him, learns new skills, and obtains allies. This is usually the slowest part of a story. The midpoint is an important event that (1) re-engages the audience somehow (often by raising the stakes or by increasing the opposition dramatically), and (2) forces the protagonist to change his methods, usually from responsive to proactive. Tension then continues to rise. At the ‘pre-second plot point lull’, the protagonist hits an all-time low, when things can’t seem to get worse. There is usually a short period of despair (sometimes called the ‘dark night of the soul’). Then, we reach the second plot point, which is where the protagonist obtains the last important piece of information that he needs. This signals that the story has turned a corner, and you can feel the end approaching.

Syd Field identified Act 3 as the Resolution, which constitutes about 25% of the story. It starts with the protagonist gathering his strength for one last struggle with the opposition. The chase begins (the pace will be much faster now and won’t let up until the struggle is over). We finally get to the epic climax, when tension is at its highest. Then we get some form of resolution and aftermath.

Three-Act Structure

Act 1: Setup

Hook

Introduce protagonist and setting

Inciting incident (gets the story moving)

First plot point (point of no return)

Act 2: Confrontation

Problems mount / character development

Midpoint (raise stakes, protagonist changes)

Disaster and Despair

Second plot point (last important revelation)

Act 3: Resolution

Chase begins

Climax

Resolution and aftermath

Does the Raiders Opening Follow This?

The opening of Raiders may not follow this structure to the letter, but few films do. They do follow it closely though. Let’s take a look.

Three-Act Structure Diagram by Studiobinder

In Act 1 of this opening, we do not seem to start with a reluctant hero, safe at home in his mundane life. Remember that this opening is not a full-length movie, so it needs to get moving quickly (more on that below). Yet, it does start with Indy looking at distant hills and mountains from relative safety. It introduces Indy by making him a mysterious figure. He’s a brave and knowledgeable leader. It also introduces the setting by showing Indy’s hirelings, the thick jungle, and the hirelings’ fear. It also introduces the dreaded Hovitos, and the statue that terrifies the porters seems to indicate that this is their territory. A caption gives us time and place. The inciting incident is least obvious to me, but it may be when the porters flee, for it signals that Indy has reached the area that he was seeking. Barrancas’ treachery is used as character development, displaying Indy’s awareness, calm, and skill. Act 1 ends with Indy and Satipo outside the entrance, discussing its dangers. In a classic story, the hero has doubts, but here it is Satipo. Still, Indy has a chance to turn back before crossing the threshold. He chooses to enter the temple, and his life will never be the same.

In Act 2, problems mount in the form of spiders, light-triggered traps, the knowledge that even the talented Forrestal died here, a pit trap, and the potential for many dart traps in the idol chamber. We see more character development, as Indy aids his bumbling hireling three times, showing his character. We see more signs of his knowledge, agility, and daring. The midpoint arrives when Indy reaches the stone pedestal that holds the idol. Up to this point, he has been largely reactive and careful. He defended against Barranca’s treachery, he brushed off spiders, he avoided a spike trap, and he side-stepped many dart traps. The first half of Act 2 ends with Indy swapping the sand for the idol.

Then the stakes become much higher, for the idol chamber collapses. Indy has to be proactive and rash to survive, charging through the darts. The pit presents a problem, and a closing stone door threatens to seal him in the temple. Satipo then betrays him, marking the disaster (betrayal is a classic occurrence at this point in the three-act structure). At his lowest point, he hangs from the edge of a pit, about to be sealed in an ancient tomb, abandoned and likely forgotten. Even the root that he grabs gives way. However, he barely manages to climb up and to roll under the stone door. Indy recovers the idol, flees from a boulder, and exits the temple, only to find himself face-to-face with the dreaded Hovitos, who finally make their appearance. Indy is clearly beaten, and we get a few seconds of despair. Belloq then appears and reveals himself as leader of the Hovitos. This seems to be the second plot point, when the hero learns the last bit of needed information. He now knows his foes’ location and their leader; there are no more surprises.

Act 3 of this opening begins with a chase. As this is just an opening, Indy will not physically confront Belloq or the Hovitos here. Instead, the climax of this mini-story comes with Indy’s refusal to give up (he may have lost the idol for now, but he will not die there). He runs, and the Hovitos give chase. For a resolution, we are satisfied to see Indy escape unharmed. Yet, since this is also the opening to a film, we are unsatisfied because Indy lost to Belloq, something that the end of the full film will fix for us.

I now have no doubt that Kasdan purposefully used the three-act structure to make this opening better than most. In less than thirteen minutes, he walks us through a full story, with all the narrative elements that make a story satisfying, deviating slightly only a few times because this is just an opening to a full-length movie. Might we use this structure, as well as some other tricks used by Kasdan, to make our RPG openings better?

Openings in RPGs

I’d like to avoid confusion here. What exactly do we mean by openings? I see three basic types.

Types of RPG Openings

- For a new campaign…

use a short adventure as an opening - For a new adventure…

use a single gaming session as an opening - For a single gaming session…

use an opening of about thirty minutes

First, in the case of an entirely new campaign, the opening might be a short, stand-alone adventure of a few gaming sessions.

Second, in the case of a new single adventure, the opening could be the first gaming session of that adventure (my own gaming sessions usually run for about four hours).

Third, in the case of a single gaming session of about four hours, the opening could be a series of very short encounters, running for a total of about 20-30 minutes.

In this article, I’m exploring the idea of turning an opening into a complete mini-story by roughly following the traditional three-act structure (as Kasdan did with the opening of Raiders). Because a stand-alone adventure, as an opening for a new campaign, should already be a self-contained story, I don’t think we need to consider it here. Instead, I want to focus on (1) a single-session opening for a new adventure and (2) an opening series of encounters for a single night’s gaming session. It might not dawn on many DMs to try to make those openings into self-contained stories using a three-act structure (it certainly didn’t dawn on me until I read Thallon’s article). The rest of this article examines how we might do that.

Brief Detour

Though it’s not my focus in this article, there are several interesting ways to start a new campaign. Guy Sclanders from How to be a Great GM put out an interesting video called Top 10 Campaign Starters on Sep 18, 2020. Check it out if you wish.

Ideas/Tips to Borrow for RPG Openings

Before we look at ideas and tips to glean from Kasdan’s opening of Raiders, we should be clear on what we are NOT trying to do:

- We are not looking to convey information with the camera, as movie-makers do. Thus, in my breakdown above, I ignored camera shot size, shot framing, camera focus, camera angle, and camera movement. Though these are interesting and allow screenwriters to play on the audience’s emotions, I see little relevance to RPGs, for even detailed DM descriptions still manifest differently in each player’s mind.

- We are not trying to develop the main characters of our story. The main characters are the PCs, and it’s the players job to do that. To be specific, we will NOT tell the PCs about their history or future (what they’ve done or what they will do). If you wish to work with a player to create a good backstory or to set goals that the PC can work to attain, that’s great. However, as DM’s that are creating an opening for an adventure or session, we are not planting memories that we want the PCs to have but the players do not. That’s weak. In Raiders, the writer, using only a few lines, creates two long-standing rivalries with Forrestal and Belloq. You may want to introduce a rival in an opening, but do not try to fabricate a long-standing rival out of thin air. It likely won’t have the impact that you seek, for no matter what you say, the player has no history with this rival. In short, we should not use narration to flesh out PCs (though we may be able to borrow some screenwriter tricks to develop certain NPCs).

- We are not trying to make the main characters mysterious, as screenwriters can. If the players want their PCs to be mysterious, they should make them so (I’m not sure it’s a great idea, but that’s beside the point). Yet, we may be able to borrow screenwriter tricks for use on certain NPCs.

- We cannot move the story along as fast as screenwriters can. Don’t try to match their speed. They do not have to deal with players, who often seem hell-bent on doing the precise opposite of what you hope that they’ll do. We can nudge the story in a certain direction or toward a better speed, but trying to time the encounters in your opening has proven highly frustrating and seldom worth the effort.

Screenwriter Tricks to Ignore in Writing a Three-Act Opening

(1) Using camera tricks to tell the story

(2) Developing main characters (PCs)

(3) Making main characters (PCs) mysterious

(4) Using precise timing

Ok. Let’s get to the tricks that we can indeed borrow. I’ll try to incorporate the tips into a three-act structure, placing them where they may be most useful.

Act 1: The Setup

Dedicate roughly 25% of your opening to Act 1. Set the scene, quickly but vividly. No need to introduce the main characters (the PC), but you can highlight an important NPC here.

1. Cementing

I cannot for the life of me recall where I first heard this term. Suffice to say that I did not invent it. It usually refers to openings, though I imagine that a skillful DM might cement an ending too. You ‘cement’ an opening by fixing certain aspects in stone before play begins. For example, if the adventure is designed as a monster hunt in a jungle, you would not start the action at a tavern, where PCs have every opportunity to go in the wrong direction. Instead, you start the adventure after the PCs have decided to kill the monster (how far after is up to you). Though you can still give PCs plenty of options during the adventure, this technique lets you forbid choice in the one spot where it is undesirable. In the opening of Raiders, Indy has already decided to seek out the golden idol.

2. In Media Res

This Latin term, which translates to “in the middle of things”, is the practice of telling a tale, not from the beginning, but after the tale has begun. This is usually done to dispense with the mundane and boring events at the start of most stories (in the case of an adventure, this includes the planning, shopping, packing, and traveling through civilized areas). In the opening of Raiders, Kasdan starts the story in the Peruvian jungle, not at a university in the US. This immediately gets the audience’s attention, for we wonder “What is this place?”, “How did we get here?”, “What are we doing here?”, etc.

Many DMs use this to good effect by starting play with a battle. “Roll for initiative” starts the fun right away. However, you need not start with combat to do in media res. Like the opening of Raiders, many old-school tournament modules (like the famous G1: Against the Giants or A1: Slave Pits of the Undercity) begin just before the PCs arrive at their destination, which is often a dungeon or monsters’ lair.

You can start in media res, regardless of whether you use cementing. The opening of Raiders combines them, which brings the audience to the action the quickest. However, you could start an adventure with a battle in media res, and then dangle the main plot hook to PCs afterwards, dispensing with cementing.

3. Paint a Vivid Picture

This tip is not exclusive to the three-act structure, but Kasdan uses it effectively, and it’s much more important to DMs than to screenwriters, so we’ll mention it here. Though you don’t want to try to paint the PCs in a certain light, you can use vivid descriptions to describe an important NPC, if that suits your purpose. With your words, you can also give players a strong feel for the setting. Try to use all five senses. With modern electronics, it’s easy to play a soundtrack or sound effects (jungle sounds, for instance) in the background. I always find touch and taste to be the most challenging. For touch, remember that it doesn’t always mean what you feel with your hands. Your boots might drag heavily as you slog through mud or snow, a heavy pack may chafe your shoulder after many hours, etc. For taste, you might briefly mention food or drink, but sweat might also run into your mouth, and after battle, so may blood. For an opening though, the key is to paint a vivid picture quickly. Kasdan’s opening of Raiders could serve as a clinic on writing efficiency. Include as many elements as you can, but don’t wax poetic. Look to get maximum punch for every sentence.

4. Hint at Previous Hardship

When you use cementing and start in media res, you run the risk of losing the epic feel of a long adventure (because you skipped the whole beginning). This is acceptable, but there is a way to hint at the long section that you skipped, thereby giving players some appreciation of the journey’s hardships. This increases the believability of the story. In the opening of Raiders, Kasdan shows the hirelings as fatigued and sweat-stained. He makes no mention of how long they have been in the jungle (he doesn’t have to). The porters and the pack animals also suggest a long, arduous journey. It costs a writer (or DM) nothing to add this flavor, and subconsciously, it gives a sense of history where there is none. An NPC might complain of sore feet, another might thirstily drink from a wineskin, and still another might dump some water on his head. You get the idea.

5. Hint at Unseen Dangers

Foreshadowing builds tension. Kasdan has us afraid of the Hovitos long before Indy tumbles out of the temple. The fear and anger in Barranca’s voice in the beginning, the porters running away in terror, the poison dart in the tree, the Peruvian guides always looking behind them, and Barranca’s assessment (“we’d be dead already”) all build up the Hovitos as a deadly threat. Kasdan also hints at the many dangers in the temple with Satipo’s comment (“no one has come out of there alive”) and by noting that the talented Dr. Forrestal died there. Once inside, the webs hint at the spiders. Later, Kasdan hints at the unseen traps in the idol chamber by allowing Indy to find a soil-covered pressure plate, by showing dozens of similar ones on the floor, and by showing many carved stone faces on the walls, each of which may fire a poison dart. Again, what makes Kasdan so good with this opening is how efficiently he does all this. I noticed that he tends to use many small and subtle hints instead of one long-winded and detailed one.

6. First Plot Point (Point of No Return)

Even if it’s very brief, throw in some sort of threshold for the PCs to cross, literal or symbolic. Since PCs are unlikely to have doubts, do what Kasdan does and have an NPC express serious reservations about going forward. It may actually get players to consider consequences for all of three seconds. The goal is not to stop the adventure, but to make it seem more realistic. Normal people hesitate in the face of danger, at least momentarily.

Act 2: Confrontation

Dedicate roughly 50% of your opening to Act 2.

In general, throw many small problems at the PCs before jacking up the stakes and making success seem impossible.

Hint at Unseen Dangers

7. Use a Variety of Challenges

The opening of Raiders presents Indy with a variety of challenges, allowing the writer to display several of Indy’s character traits. In an RPG opening, using a variety of challenges pays several dividends. If you wish to develop a key NPC, you’ll be able to show off several traits in quick succession. You’ll need to keep each one brief though (perhaps one skill check or two will suffice for each). I would not use a large melee in my opening, as it will consume most of your allotted time. The opening of The Mummy (in which you meet the main character) falls into this trap. Though well-filmed and exciting as a battle, it shows us little about the main character. The opening of Tomb Raider suffers similarly, though it does not feature a large melee. Instead, Lara Croft fights one robot that just won’t die. Honestly, I was bored after about one minute. Just as I would avoid a big melee in a three-act opening, I would also avoid a monster with 400 hit points, damage reduction, and magic resistance. Opt for several small challenges instead.

8. Provide Some Gratification

In just a few minutes, Kasdan introduces the mystery of Forrestal’s disappearance and then reveals the secret (he died on spikes in the temple). He gives us Satipo’s treachery, and then he shows us how he paid with his life. He shows us Barranca’s treachery and how he too perished. Last of all, though Indy fails to get the idol, he escapes from certain death at the hands of dozens of deadly Hovito warriors, deep in Hovito territory. For that last example, the level of gratification is not meant to be equal to that at the end of an entire adventure (it’s only an opening), but giving the audience some gratification (like Indy escaping) is a lot better than providing none. If you haven’t considered player gratification for your opening (figuring that the players have the rest of the adventure to obtain their gratification), try adding a bit here too.

9. Midpoint

The midpoint is where screenwriters re-energize the audience. The main characters usually change their mindset and approach, but in an RPG, the DM should not tell players what the PCs feel or how they should act. Instead, jack up the stakes. This should make the players lean in and get more engaged.

10. Disaster/Despair

The disaster is where everything goes wrong for the main character. It’s the lowest point. It’s easy to go wrong here. If you make a trap too deadly, you’ll simply kill the PCs, and this is just an opening (the adventure has barely begun). If you try to arrange for seeming disaster by throwing an unkillable monster at the PCs, you’ll fall into the ‘Tomb Raider Trap’. Start a large-scale battle and you’ll fall into ‘The Mummy Trap’. Instead, consider a situation that seems impossible but actually isn’t. In Kasdan’s opening, Indy was betrayed by a hireling (DM can script that), on the wrong side of a pit and without the means to cross it (DM can arrange that), while a stone door started closing to seal him into the temple (DM can arrange that). Yet, to escape, he merely had to jump the pit, pull himself up, and roll under the closing door. Though not easy, he doesn’t have to fight a battle, in which so many things can go sideways. Also, be sure that a failed check will not spell doom. Indy may have failed that jump check, but he caught the edge. He may have failed to pull himself up (the root became loose), but he gets a second chance. Remember that this is just an opening, so the PCs should be allowed to survive. Make it exciting though!

Low Point: The Pit of Despair

As for despair, again the DM should not tell PCs how to feel, but a sharp DM can orchestrate those feelings by playing with expectations. Kasdan had us hoping that Indy would succeed and had us believing in his abilities, only to show us that Belloq outwitted him this time.

11. Second Plot Point

Consider taking just a moment to reveal one last bit of important information to PCs. The tough question becomes “What should I reveal?”. This tip may help: How the PCs react to that information should bring us right into Act 3, where everything speeds up. Therefore, consider what information would force your PCs to climb out of the pits of despair and start swinging again. My mind flashes to an old adventure of mine, in which an anti-party was working against the party during the entire adventure. The lowest point for the PCs came when they returned to their base (their safe haven), only to find it on fire and half of their hirelings and henchmen dead. It took them a few hours to figure out what happened, but then they found that one of the trusted hirelings was actually an anti-party spy, who poisoned the others and set fire to the house. The PCs were out for blood after that. Not only did that event play on their emotions properly, but the disaster (the poisoning and the fire) were DM-controlled elements that would not drag out or kill the PCs.

Act 3: Resolution

Dedicate roughly 25% of your opening to Act 3.

12. Pick up the Pace

Continue to throw diverse challenges at the party, but pick up the pace considerably. The start of Act 3 is often called ‘the chase’ for a reason. If you can incorporate an actual chase, then great. This is touchy though, for, unlike a screenwriter, you cannot guarantee that the main characters ( PCs) will flee or give chase. An important NPC could hold the key. As enemies swarm over the horizon, a leader type could order everyone back to a ship, for example. A wounded NPC leader may require evacuation. Alternatively, the PCs themselves may be too valuable to risk in battle. If playing a sci-fi adventure, perhaps one PC is the ship’s pilot (if he dies, everyone would likely die). Another useful idea is revealing a time limit before something dreadful happens. Perhaps the PCs’ current location will explode (in a sci-fi adventure, perhaps the self destruct mechanism was activated), or perhaps the PCs must get back to X in time to rescue someone.

13. Consider a Mixed Resolution

The finale brings some sort of resolution to the problem. The PCs can succeed, getting gratification. However, consider allowing them to fail in their overt goal, much as Indy did. This is just an opening, so you might be able to make a grand PC success possible at the end of the full adventure. In short, ‘Keep ‘em hungry for more’.

14. Touches of Comedy

Many years ago, I was fortunate to play in a game run by a very popular DM in Albuquerque, NM. There was actually a waiting list to get into his game. I learned much from him, but one tip was to add some comedy to every session. He noted that players, years later, may not recall what their PCs were doing, but they’ll fondly remember laughing a lot at the table.

The Chase: Pick up the Pace

Though you can add comedy as you create the above material, it doesn’t come naturally to me. I would probably get through all of the above and not have any. In such a case, I would go back to the start and look to weave in a few fun elements. How much you should add depends on the desired tone of your adventure, but even grim stories need some comedy to relieve tension. It need not be slapstick. It can be subtle. In Raiders, Satipo provided two laughs, first by turning to reveal that his back was covered with spiders (plus the look on his face as a tarantula crawled across his neck–that could not have been scripted). Second, he uttered his famous line, “If you insist, señor.” Belloq is mildly funny too, agreeing with Indy’s shady appraisal of his character. Of course, we then have the sight of Indy running toward the plane (which is not funny), only to see a swarm of Hovitos appear behind him as they crest the hill. Indy’s pilot, Jock, then provides the last two laughs, debating for a moment whether he should let go of his fishing rod to help Indy and finally telling Indy to “show some backbone”. That last one is easy to copy, given that the PCs have likely just risked their necks several times.

Screenwriter Tricks to Try in a Three-Act Opening

Act 1

(1) Cement the opening

(2) Start ‘in media res’

(3) Paint a vivid picture with few sentences

(4) Hint at previous hardships

(5) Hint at unseen dangers

(6) First Plot Point (point of no return)

Act 2

(7) Use a variety of small challenges

(8) Provide some gratification

(9) Midpoint (raise stakes)

(10) Disaster/despair

(11) Second Plot Point (last new information)

Act 3

(12) Pick up the pace

(13) Consider a mixed resolution

Extra (layer it in afterwards)

(14) Add touches of comedy

Well, that’s as thorough a breakdown as I can write. Kasdan’s opening in Raiders is acknowledged as a masterpiece. While recognizing that RPGs are different from novels and films, I do think that we can use some of Kasdan’s techniques to improve our games, namely the openings (at least some of them). I’d like to try this in my next few adventures or sessions. I won’t force it where it doesn’t seem to fit, but I will be alert for an opportunity to try a three-act opening. If I manage to write one, perhaps I’ll describe it in a follow-up article. If you write one, please share it with us. Iron sharpens iron.