This is Faith in Play #21: Villainy, for August 2019.

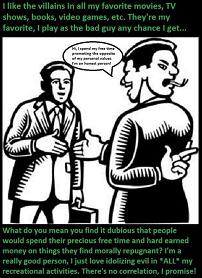

It was a year ago, but I had a stack of articles in the queue when it happened, and decided not to disrupt the plan by answering what appeared to be a question from a Troll posted to our Facebook page (I managed to lose the link to the thread). It was comprised primarily of the image below, and the question of what we think of it.  I think Facebook is a terrible place to attempt to hold serious discussions, but Bryan pointed him to Faith and Gaming: Bad Things, about evil in the world, and I suggested Faith and Gaming: Bad Guys, about playing the wicked character as a way to bring faith into the game. I did not get a response to that, but I felt that there were valid concerns raised by the picture (I think that calling it a “meme” was wishful thinking on the part of whoever created it), even if it might have been posted by a troll.

I think Facebook is a terrible place to attempt to hold serious discussions, but Bryan pointed him to Faith and Gaming: Bad Things, about evil in the world, and I suggested Faith and Gaming: Bad Guys, about playing the wicked character as a way to bring faith into the game. I did not get a response to that, but I felt that there were valid concerns raised by the picture (I think that calling it a “meme” was wishful thinking on the part of whoever created it), even if it might have been posted by a troll.

If you can’t read the text, above the image it says

I like the villains in all my favorite movies, TV Shows, books, video games, etc. They’re my favorite, I play the bad guy any chance I get.

The text balloon in the image itself then shows the two-faced person saying

Hi, I spend my free time promoting the opposite of my personal values. I’m an honest person!

At the bottom it then continues

What do you mean you find it dubious that people would spend their precious free time and hard earned money on things they find morally repugnant? I’m a really good person, I just love idolizing evil in *ALL* my recreational activities. There’s no correlation, I promise!

And we are thus faced with the issue of whether someone who plays the villain at every opportunity is reflecting his true values and only pretending to be good in his regular relationships. In a sense, which version of him is a role, and which is the reality?

This is the more potent a question for me, because as a novelist I am constantly creating the characters on the page, working out what they would do, and I have to understand them–and as I noted decades ago in a journal somewhere, I understand them because I find them inside me, facets of my own personality, my own identity, people I could have been, in a sense could be. Sure, there is a degree to which I sometimes model characters after people I know, and thus I can ask myself what would Chris do, or John, or Ed, or any of the many other people whose identities contributed something to the composites that are my characters, but this only removes it slightly: in order to understand Chris or John or Ed well enough to know what they would do, I have to find that part of me that resonates with them, in essence discovering them within myself, knowing what it would be like to be them. So I am the heroes, but I am the villains, and the ordinary people between the extremes, the background characters, the important mentors and sidekicks, all, everyone, is found as part of who I am somewhere inside. I have wickedness in me, enough to understand what motivates the wicked.

Arguably, though, I don’t always play the villain–that is, I don’t play the villain exclusively. Yet I understand the villain, and I understand the appeal of playing him. I prefer to be the hero, but I know people who usually play the villain, the thief, the rogue, the scoundrel. (I know people who usually play the hero, as well, but that’s not the issue here.)

As we noted before, there are admirable qualities, lessons to be learned, from playing the rogue. There are also ways, as discussed in those previously listed articles, to use playing the wicked as a means of throwing light on the truth, of bringing our faith into our games. Not everyone who plays the villain, even who plays the villain regularly, does so because he is secretly a villain at heart. It is possible that a particular individual finds that playing the evil character is the best way for him to show his companions just how wicked they are, and how much they need salvation. There can be good reasons to play the bad guys.

None of which completely addresses the objection. That is, there might well be players out there who want us to see them, in themselves, as basically good people, but who always love the villains and always play the villains because there is something in them that wants to be the villain.

There is that in all of us, I think. We are all born sinners, selfish people who by game standards would be evil. We like being selfish; it makes us feel good to think that there is someone who always puts us first, even if that someone is actually us. Yet the critic is right. If we enjoy that in our recreational activities, are we feeding something that we ought to starve in our real lives? Are we pretending to be what we really want to be, instead of really wanting to be sons and daughters of God?

I think there are good reasons to play bad people. They include trying to understand how sinners think so we can reach them, trying to show sinners the wickedness in their own lives, creating the contrast between good and evil so that the choice is made clear–there are certainly other good reasons to play the bad character. The question, though, comes to our motivation: do we really want to be the bad person, or are we doing this for a good reason?

So examine yourself to see if you are in the faith, and remember that whatever a person sows he will also reap.

Previous article: The Problem with Protests.

Next article: Individualism.