Last month’s installment of Faith and Gaming, Making Peace, was the twelfth in the series. We’ve been talking about the integration of faith and gaming for a year now; and that in itself could be a call to go back to the beginning and consider our basic purpose. But I recently read these words in a public forum, from a Christian who is a gamer; and this idea (edited for punctuation and grammar) also brought me back to the preliminaries we discussed a year ago, the basic reason why we’re talking about faith and gaming at all.

I’ve never been terribly fond of Christian games, though, to be honest with you, partly because I think that the subject matter is where I draw a line between fantasy world and reality. I don’t want to put my Christianity on the shelf with my gamebooks. I keep my Bibles in a different bookcase…

I agree, but I disagree.

I’ve never been terribly fond of Christian games, either; but I think that’s because I always feel like they’re trying to pound me over the head with some particular aspect or brand of the faith, and I don’t need that. C. S. Lewis, who wrote many Christian books, wrote in one that we didn’t need more Christian books; we needed more books by Christians. Arguably, this is what his Narnia series and Space Trilogy are: books by a Christian, books which are intended for everyone and which are not intended as Christian polemics or arguments or defenses or discussions, but are just books which reflect within them a Christian world view but don’t pound it home like some camp meeting evangelist. I would much prefer a game which isn’t trying too hard to be Christian, but which quietly reflects the faith of its author.

But I don’t want to put my Christianity on a different shelf from my game books. I thoroughly believe that our faith is not some independent plug-in component of our lives, but is in fact the core truth of our lives, the thing about which all of our life is, around which all things revolve. That means that whether I’m playing Multiverser or D&D or Vampire: the Masquerade or bridge or pinochle or poker or Monopoly or whatever, there is a level somewhere in what I’m doing which is informed by my faith, which is transformed by my faith.

Lewis wrote a wonderful book entitled The Screwtape Letters. Many years later, a prominent evangelical author attempted to do a sequel. The review I read of the sequel was scathing. The book, it was said, trapped Screwtape into the mindset of a very narrow Americanized Evangelicalism; instead of being about universal principles of how to live a Christian life against the temptations of the wicked one, it was about those strange concerns American Christians seem to have about makeup and movies and other cultural connections. And that’s what I don’t like about most “Christian” things: they are too tied to “my idea of Christian conduct” and not to what it really is to be Christian.

I do think that there are a lot of Christian gamers out there who not only feel like they have to hide their gaming, they also think they are the only ones, and even wonder if they’re crazy or actually in danger of losing their salvation because of a hobby that seems perfectly all right to them, perhaps that they even feel God encouraging them to enjoy, but is condemned by every Christian they know. I get letters from these people all the time, thanking me for my writing, just because they are encouraged to know they aren’t crazy. So yes, a presence for the Christian Gamers Guild helps these people. It also helps the image of the Church among gamers—so many of them think we’re narrow-minded haters of everything and are very surprised to find out that not only do most Christians not hate them for their gaming or think God has consigned them to hell for their hobby, but some of us actually would enjoy having them over for a game.

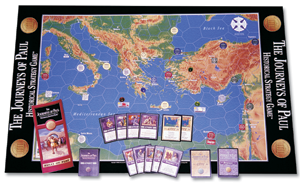

There certainly is a place for Christian games. That place is much the same as the place for Christian books: in the enclaves to which Christians retreat for fellowship and encouragement. Christian games are for youth groups and retreats, for Christian families and Christian friends, and for any other group that is intended in some sense to be exclusive—exclusive in the sense that others are welcome if they want to be immersed in the world of Christian faith and practice, but their antichristian and unchristian ideas are not. In such places, Christian games should have a home. But as Lewis said about books, the world does not need many Christian games. The world, in fact, does not need any Christian games, for such games are not for them, but for the church. The church needs only a few good ones which entertain and edify. The world needs more games by Christians, games which quietly reflect the faith of their authors without driving off the gamers.

Those games are not easy to write; and it is not easy to convince many Christians that they are good things. Too many of us want to use games (or music or art or movies or any other thing) as a billboard, bait to bring people close enough that they can’t run away fast enough to avoid hearing the gospel, rather than to let them do their work of quietly undermining the unbelief of those who are drawn in to enjoy them until they realize the truth that has been staring them in the face all along. But it is those games, and not games which demand you understand the gospel or the Bible or the personal code of conduct of the author, which will bring people to faith. Those are the games we need.

This article was originally published in April 2002 on the Christian Gamers Guild’s website. The entire series remains available at its original URL.