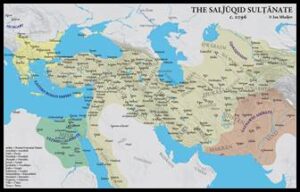

The Seljuk Sultanate circa 1096 (light brown)

Historical Context for the Hollywood Films

Kingdom of Heaven and Arn: Knight Templar

Preface:

I Initially wrote this article for my medievalist friends, who recreate an order of soldier-monks in the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA). They often show new recruits The Kingdom of Heaven (2005) and Arn: Knight Templar (2007). At some point, they asked me to write about the history leading up to the action in the movies. I quickly found that it’s a much more difficult task than one might think. I was fairly well-versed in the history already, but I have never written about this particular tale. Very quickly I saw the dilemma facing Hollywood writers. The historical tale is very complex, so even in an attempt to make it as plain as possible, I ran into trouble. I was tempted to explain in detail all of the complexities, leaving the reader with a full understanding of the period just before 1187. Yet, that would have ballooned this article into a text of over a hundred pages, and that was not my aim. At times, I was tempted to chop out anything not immediately relevant to the movies, but this would leave the readers with very little appreciation of the amazingly rich saga. I see why Hollywood producers, whose primary goal is entertainment and not education, choose instead to change six dozen details in the story, thereby simplifying it for the screen. Faced with this dilemma, I recorded as much historical detail as I could without really going into the weeds. This really amounts to mentioning a lot of detail in passing without expanding on it much (unless it’s critical to the main story).

Background

Islam originated in seventh-century Arabia and spread like wildfire into adjacent territories. By 749, the successor of the Prophet Muhammad, using the title of caliph, ruled a vast theocratic state from Baghdad. It included the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, North Africa, much of the Iberian Peninsula, Syria, the whole of Mesopotamia, and all of Persia. In 750, assassination and dynastic rivalry rocked the caliphate, and the Islamic world saw its first political division when a separate caliph emerged in Cordoba, breaking all of Iberia from the unified empire. Later, a third caliph emerged in Tunisia, this one espousing the beliefs of the Shi’a minority.1 His armies conquered much of North Africa and eventually conquered Egypt in 973. Though the Islamic world was politically and religiously fractured at the end of the tenth century, it was entering a golden age.

Independent Turkish States on the Frontier circa 1071

The caliphs of Baghdad and Cairo grew weaker in the eleventh century, especially as nomadic Turkish horsemen, migrating from central Asia, appeared in great numbers. As the Turks gradually converted to Sunni Islam, they supplanted the Arabs as the leaders of the Islamic world. Then, two Seljuk brothers from Persia founded the beginnings of a great Seljuk sultanate in 1037. They went on to conquer all of Persia, Mesopotamia, Syria, and eastern Anatolia. By 1055, a Turkish sultan in Baghdad effectively ruled the caliphate in the name of the caliph.2 This Seljuk army then crushed a Byzantine army at Manzikert in 1071, revealing the weakness of the Byzantine Empire and sending shock waves across Christendom.3 In the aftermath of Manzikert, the Turks overran the rest of Anatolia. The Byzantine capital of Constantinople (the second Rome), though protected by triple walls and a powerful navy, lay just across the Hellespont. The Seljuk sultanate reached its zenith in 1092. At that time, it stretched from the eastern reaches of Persia to the Aegean Sea in the west, from the Black Sea and Caspian Sea in the North to the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf in the south.

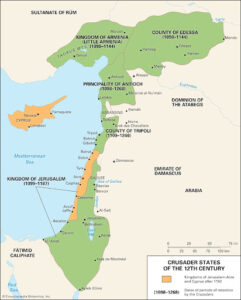

Four Crusader States circa 1109

The advance of these powerful people caused the Byzantine Emperor, Alexios Komnenos I, to send delegates to the Council of Piacenza in 1095 to ask Pope Urban II for aid.4 The Pope responded favorably, traveling to his French homeland to muster support. This effort culminated in the famous Council of Clermont, which marked the start of the First Crusade. However, even before the Emperor sent his envoys to Piacenza, the Seljuk sultanate was starting to crumble. Back in 1077, a Seljuk relative of the sultan had formed an independent sultanate of Rum (Rome) in Anatolia. An emir of the Turkish Danishmend dynasty established an independent state in Anatolia as well. Then, when the Sultan Malik Shah died in 1092, his family members fought each other for control, splintering the sultanate into several small states. It was during this time of strife that Christian crusaders marched into Syria, captured Jerusalem, and carved out four separate Latin states—The Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the County of Edessa.

Arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Crusaders did not enjoy their success for long. In 1144, a Turkish ruler named Zengi, the atabeg of Mosul, conquered the Crusader County of Edessa and triggered the Second Crusade.5 Then, in 1154 Zengi’s son, a powerful Turkish warlord called Nur ad-Din, managed to unite the states of Aleppo, Mosul, and Damascus, bringing all of Muslim Syria under his rule. In theory, he paid homage to the sultan, but he was effectively independent. He had the blessings of the Sunni caliph in Baghdad, and he successfully fought against the Crusaders during the Second Crusade (1147-1150). He then turned to the situation in Egypt. The Fatimid dynasty had ruled a Shi’a caliphate there since 969. This Egyptian caliphate had been at odds with the caliph in Baghdad since its creation. By the twelfth century, the Fatimid state in Egypt was wretchedly weak, paying tribute to the new Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Having already united Syria, Nur ad-Din planned to turn his full attention to the enemy Crusader states. However, Egypt had become a problem. The Egyptian ruler was often subservient to the King of Jerusalem, and his very existence was an insult to the caliph in Baghdad. In 1164, Nur ad-Din dispatched his powerful general, Shurkuh, to prop up a Fatimid puppet in Cairo. Shurkuh was successful, but the puppet soon grew tired of the arrangement. By 1171, Shurkuh and the puppet were dead, and Shurkuh’s talented nephew, Salah ad-Din (or Saladin), had taken full control of Egypt, having put down several revolts. He then abolished the Fatimid Caliphate, restoring Sunni Islam to Egypt and restoring spiritual control to the caliph in Baghdad.

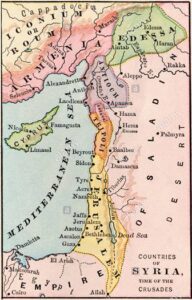

Crusader States of Outremer circa 1174

By this time, the Seljuk sultanate had completely fractured. Back in 1141, Sultan Ahmad Sanjar had led his army against forces on his eastern border. His defeat at the resulting Battle of Qatwan cost the Seljuks their eastern provinces. When the sultan finally died in 1157, many local rulers, including several atabegs of Syria, asserted their independence. That same year, the caliph of Baghdad defeated Seljuk forces in that city, gaining some local control in Mesopotamia.

Saladin and the Leper King

In 1174, Nur ad-Din began mustering a great army in Syria, supposedly to crush his upstart general, Saladin, though the latter had been careful to pay tribute to Nur ad-Din. In any case, Nur ad-Din grew ill and died before his army could march. Saladin then took advantage of the inevitable squabbling between Syrian dynasties. When one atabeg invited him to intervene, he marched into Syria and united the entire area with Egypt. The caliph in Baghdad gave his blessing, dubbing Saladin the ‘King of Egypt and Syria’. Desmond Seward, author of The Monks of War, calls Saladin ‘a Kurdish adventurer that hacked his way to the throne’. Yet, he also compares him to St. Louis, the famous French crusader king, noting that Saladin lived like an ascetic—fasting, sleeping on a rough mat, and giving alms unceasingly.6 Romanticized by the Franks, loathed by Shi’a Muslims, and hailed by the Sunni, Saladin hoped to unite the Muslim world.

Arms of the powerful Courtney Family

On hearing of Nur ad-Din’s death in 1174, King Amalric I of Jerusalem led a force against the Saracen garrison at Banias, on the Kingdom’s northeastern frontier.7 He eventually gave up the siege and fell ill from dysentery, dying that July. The King’s first wife, Agnes of Courtenay, had given him a son and a daughter (Baldwin and Sibylla), while the King’s second wife, Maria Komnenos, had given him a daughter (Isabella).8 Amalric’s son, Baldwin, was only thirteen when his father died, and only a year earlier, the boy’s doctors had discovered that he had leprosy. While he remained a child, rival factions within the Haute Cour, the powerful parliament of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, schemed to control the regency. Miles of Plancy served at first, but Count Raymond III of Tripoli (the late king’s cousin) supplanted him.9 In the king’s name, Raymond signed a peace treaty with Saladin. No one expected the young king to survive for long, so scheming continued to control the marriages of Baldwin’s sister, Sibylla, and half-sister, Isabella. The young leper king surprised them all, for he reigned for over ten years, displaying great bravery, wisdom, and charisma.

Arms of the County of Tripoli

The Franks were fortunate to have such a king, for the strategic position of Outremer was deteriorating rapidly.10 Count Raymond’s regency ended on the second anniversary of Baldwin’s coronation. Instead of renewing the treaty with Saladin, Baldwin raided on the frontier. It gained him little. Then Count Raymond’s Byzantine connections seemed to lose all value, for the Seljuk Turks of the Sultanate of Rum wiped out a Byzantine army at the Battle of Myriocephalum in Anatolia in 1176. The Empire would never again substantially intervene in Syria. Then, in 1177, King Baldwin arranged for his sister to marry William of Montferrat, cousin to both the king of France and the Holy Roman Emperor. The hopes of powerful aid from both of these sovereigns vanished when William suddenly died just months after his wedding, leaving Sibylla widowed and pregnant with the future Baldwin V. At the same time, the Kingdom of Armenia to the north was growing at the expense of the Crusader state of Antioch, and it seemed all too ready to ally with its Muslim neighbors.

Fictionalized image of the Leper-King, Baldwin IV of Jerusalem

The leper king did what he could to stem the tide. In November of 1177, when Saladin led an army of 26,000 Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Sudanese, and Mamelukes across the kingdom’s southern border, Baldwin responded with speed. Saladin used his numbers to his advantage, blockading the young king at Ascalon, while he marched on Jerusalem with his main force. However, Baldwin broke out with 300 knights. Accompanied by the Templar Master, Eudes de St. Amand and eighty Templars, they rode hard and managed to get around Saladin’s army.11 The little Christian force awaited him in the ravine near Montgisgard. With the Bishop of Acre holding the True Cross, the leper king and “his heavy Frankish horsemen smashed into the Egyptian army. It was a bloodbath, and Saladin fled with his troops into the Sinai Desert, where they almost perished from thirst.”12 Though two Frankish chroniclers give credit for the victory to Baldwin, Muslim chroniclers report that the head of the army that day was the bold and powerful, Raynald de Chatillon, Lord of Hebron and Oultrejordan.13

Arms of the Lord of Ibelin

Yet, the momentum had not shifted, and Saladin had his revenge two years later. Saladin had sent his nephew with a force from Syria to destroy crops and villages on the border. In June of 1179, Baldwin rode to the frontier with a large army, found a Saracen raiding party, and smashed it near Marj Ayyun. Yet, he did not expect Saladin to appear with a large army, just hours later. Baldwin and the True Cross barely escaped capture. Many blamed the loss on the Templars, who they claimed had charged too soon. The Saracens took 160 prisoners, including Master Eudes de St. Amand. Saladin offered to ransom him, but he refused, true to the Templar rule. He died in prison about a year later, perhaps due to starvation.

Arms of the Lusignan Family

In 1180, tensions flared over the hand of Baldwin’s sister, Sibylla. Baldwin offered his sister’s hand to Guy de Lusignan, but the nobles of the Haute Cour opposed the marriage. In fact, Count Raymond III of Tripoli and his ally, Prince Bohemond III of Antioch, traveled with a host of armed men to Jerusalem, ostensibly to celebrate Easter, but some suggest that their true purpose was to secure the marriage of Sibylla to Baldwin of Ibelin.14 To avert that coup, Baldwin IV hastily married Sibylla to Guy de Lusignan during Eastertide. It was a fateful choice. Now in disfavor with the King, Count Raymond and Prince Bohemond returned to their respective states in the north.

Triumvirate of Fools

Guy de Lusignan from The Kingdom of Heaven (2005): Contrary to the film, he was not a Templar

Guy de Lusignan was the son of a wealthy French lord from Poitou. At the time, Poitou was part of the Duchy of Aquitaine, held by Queen Eleanor of England. By all accounts, Guy was rash and violent. Back in 1168, he and his brothers had ambushed and killed the Earl of Salisbury, who was returning from a pilgrimage, a deed for which the Duke of Aquitaine (Richard, Eleanor’s son, later Richard I of England) banished him from Poitou. Guy’s elder brother, Aimery, had married Baldwin of Ibelin’s daughter in 1174, gaining a foothold for the Lusignan family in the court in Jerusalem. Later, the King’s mother, Agnes of Courtenay, had appointed Aimery as constable over her fief of Jaffa. He served as royal chamberlain from 1175-1178, and in 1179, Baldwin IV had appointed Aimery as Constable of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. It is unclear whether Aimery had paved the way for Guy or vice-versa, but clearly the Lusignan family’s influence had been on the rise. Thus, Guy’s marriage to Sibylla was not entirely shocking, however unpopular.

Early in 1182, King Baldwin’s health deteriorated, and he considered appointing his cousin, the newly arrived Philip I of Flanders, as his regent. However, Philip declared that he had no intentions to stay. Thus, Baldwin named Guy as regent. So unpopular was Guy that Philip protested this choice and then left the Holy Land, just one month after his arrival. For his part, Guy took the opportunity to ally with Raynald de Chatillon.

|

The Fortress of Al-Kerak In 1126, King Fulk of Jerusalem named Pagan the Butler as the Lord of Montreal (sometimes called Oultrejordan, or Transjordan in Latin). In 1142, Pagan began the construction of a strong castle atop a strategic hill that locals called ‘the Stone of the Desert’ (Petra Deserti). Pagan later made this castle (Crac des Moabites) his headquarters, replacing the stronghold at Montreal, further south. The thirteenth-century Muslim historian, Abu’l-Fida, wrote that Al-Kerak was ‘a celebrated town with a very high fortress, one of the most unassailable of the fortresses in Syria… Below Al-Kerak is a valley, in which is a thermal bath, and many gardens with excellent fruits, such as apricots, pears, pomegranates, and others.” The famous fourteenth-century Muslim explorer/historian, Ibn Battuta, wrote: “Al-Kerak is one of the strongest and most celebrated fortresses of Syria. It is also called Hisn al-Ghurab (the Crow’s Fortress), and is surrounded on all sides by ravines. There is only one gateway, and that enters by a passage tunneled in the live rock, which tunnel forms a sort of hall.” The Crusaders only held Kerak until 1188, when the garrison finally surrendered after a prolonged siege. The walls remained intact; lack of food caused the surrender. Historian Steven Runciman notes that the surrender came “after the last horse had been eaten”. |

Raynald, a Burgundian nobleman, had arrived in the Kingdom of Jerusalem back in 1153. He initially came eastward with King Louis VII of France, but when Louis left the Holy Land in 1149, Raynald remained, serving in the army of King Baldwin III of Jerusalem. The year before, Nur ad-Din destroyed a Christian army at Inab, and the Prince of Antioch was among the slain. The King of Jerusalem at the time was cousin to the Prince’s widow, and he arranged for her to remarry. Raynald accompanied the King to Antioch in early 1153 and somehow gained the widow’s hand. As the new Prince of Antioch, he lost no time in gaining enemies. When the Latin Patriarch of Antioch refused to pay him subsidies, he captured him and forced him to sit naked in the sun, covered in honey, until he relented. The King eventually intervened on behalf of the patriarch.15 In 1156, when the Byzantine Emperor failed to deliver promised subsidies, Raynald and an Armenian prince thoroughly sacked the Byzantine island of Cyprus. The Emperor invaded Armenia in 1158, and Raynald quickly sued for peace. The vengeful Emperor forced Raynald to walk barefoot and bareheaded through the streets of town, before prostrating himself and begging for mercy. In 1160 or 1161, Raynald raided into Mesopotamia, but the governor of Aleppo dispatched a force that caught him on the way back. The Saracens unhorsed him during the battle and took him prisoner. Thus, the Prince of Antioch remained in prison in Aleppo for fifteen years!16 Raynald’s wife died around 1163, and he lost his claim to the Principality. However, he had proven his relevance, and his stepdaughter (Maria of Antioch) married the Byzantine Emperor himself in 1161, while his own daughter (Agnes) married King Bela III of Hungary in 1172.17 Upon his release from captivity, Raynald quickly regained his prominence. He married the Princess of Oultrejordan, while King Baldwin IV also made him Lord of Hebron.18 His castles at Kerak and at Montreal virtually overlooked the strategic trade route between Egypt and Syria, meaning that he could disrupt trade and communication between the two halves of Saladin’s realm. Raynald was thus one of the wealthiest and most independent men in the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The Lordship of Oultrejordan (or Montreal or Transjordan)

Together, Guy and Raynald violated a truce that Baldwin IV had signed with Saladin. The chronicles name at least two raids on Muslim caravans, travelling between Egypt and Syria. When Saladin had tried to take Aleppo in 1181, Raynald drove south toward Mecca to derail his plans. Saladin had to dispatch a force into Oultrejordan to compel Raynald to return from Arabia.19 When Raynald seized a caravan and imprisoned its members in 1182, Baldwin ordered him to free the captives, but he refused. Baldwin fumed at his disobedience, an event that enabled Count Raymond of Tripoli to reconcile with the king. Raymond’s return to Jerusalem ended Raynald’s prominence, but he remained a dangerous foe.

In February of 1182, Raynald undertook his boldest and most reckless adventure. He had his men fell trees in the Moab Forest, east of the Dead Sea. They then built five ships on the Dead Sea, where crews tested them. They then dismantled the ships, packed the various parts onto camels, and rode 120 miles south to the Gulf of Aqaba, the northernmost tip of the Red Sea, where they reassembled the ships. From there, two of the ships besieged the Muslim fortress of Ile de Graye, while others raided the pilgrim route towards Medina and Mecca, terrorizing Muslims in the region. Saladin’s brother immediately dispatched a fleet, which lifted the siege of Ile de Graye and destroyed Raynald’s fleet. Saladin ordered the execution of Raynald’s captured soldiers and vowed that he would never forgive him.20

Gerard de Ridefort from Arn: Knight Templar (2007): He WAS a Templar (a crucial one at that), though he does not appear in The Kingdom of Heaven (2005)

Saladin’s power continued to grow. In June of 1183, he captured Aleppo, further consolidating his empire. Meanwhile, in September of that same year, when Baldwin IV grew very ill again, he named Guy de Lusignan as regent. However, after only one month, the King ordered his nephew, Baldwin of Montferrat, to be crowned as Baldwin V, co-king of Jerusalem. Raymond and Baldwin of Ibelin hoped that this would derail any plans on the part of Guy or Raynald to seize the throne. Raynald was not present at the boy-king’s coronation ceremony because he was attending a wedding in his own territory. Baldwin IV’s sister, Isabella, was marrying Humphrey of Toron, Raynald’s stepson.

Arms of Master Gerard de Rideford of the Temple

Saladin caught everyone by surprise and invaded Oultrejordan, looking to deal with Raynald once and for all. The local inhabitants fled in terror to Raynald’s mighty fortress of Kerak. Raynald himself barely escaped to the fortress. It is during this siege that we see a strange act of chivalry, the type for which Saladin has become so famous. Raynald’s wife supposedly sent dishes of food to Saladin, letting him know that a wedding had just occurred. Saladin supposedly agreed to cease bombardment of the tower in which the newlyweds slept. In any case, Baldwin IV and Count Raymond hastily mustered the army and marched on Kerak. They arrived on December 4, but Saladin had already departed. However, Saladin ordered a fortress built at Ajilon, near the northern border of Raynald’s territory.

The fictional character of Marshal Tiberias in The Kingdom of Heaven (2005) is based loosely on Count Raymond III of Tripoli, who held a castle on Lake Tiberias (the Sea of Galilee)

The Frankish situation worsened with the arrival of another reckless adventurer, one that would soon fall into the company of both Guy de Lusignan and Raynald de Chatillon. Moreover, this man came from the most unexpected of places—the ranks of the Templars. Following the capture of Master Eudes of St. Amand, the Templars elected as Master an elderly Aragonese knight named Arnold of Torroja in 1181. He did much to improve relations between his own brethren and those of the Hospital, and he also conducted peace negotiations with Saladin after Raynald’s troublesome raids. However, he departed Outremer in 1184, accompanied by the Master of the Hospital and the Patriarch of Jerusalem. They headed to Europe to secure recruits and donations, but he fell ill on the way and died. Thus, the Templars elected their seneschal, Gerard de Ridefort, as their new master.

Little is known of de Ridefort’s background, but he seems to have taken service with Count Raymond III of Tripoli, presumably with the expectation that Raymond would give him the hand of the heiress of Botrun, a coastal fief. However, when the lord of Botrun died, Raymond instead married the man’s daughter to a wealthy Pisan merchant.21 The date of this event is unknown. In the late 1170s, Gerard’s name appears on a royal charter, showing him as in service to Baldwin IV. He also served as the Marshal of the Kingdom of Jerusalem circa 1179. At some point, he fell seriously ill, and when he recovered, Gerard joined the Templars. This move makes sense for several reasons, but especially if his grudge with Raymond was not forgotten. Count Raymond was closely allied with the Hospital and with the Italian city of Genoa, whereas the Templars and the Venetians were often opposing Raymond. In any case, Gerard quickly rose through the order’s ranks, and by 1183, he held the position of Seneschal. When word arrived that Master de Torroja had died in 1184, Gerard de Ridefort became Master.

A somewhat romanticized depiction of Saladin in

The Kingdom of Heaven (2005)

King Baldwin IV finally succumbed to his leprosy in 1185. The court held a special ceremony for Baldwin V to celebrate the beginning of his sole reign. Balian of Ibelin carried the youth on his shoulders to demonstrate the stalwart support of the Ibelin family, which was tied by marriage to both the Byzantine royal family and to the royal family of Jerusalem. Given the child-king’s vulnerability, Count Raymond III of Tripoli served as his regent, while his uncle, Count Joscelin III of Edessa, served as his personal guardian.22 Count Raymond feared to serve as guardian, for he had a legitimate claim to the throne, and if something befell the young monarch, he would be blamed. Even Baldwin’s paternal grandfather, Marquess William V of Montferrat, left France to support his young grandson.

Despite the support that he received, young Baldwin V was sickly and died in Acre in August of 1186. Count Raymond and Baldwin of Ibelin immediately summoned the nobles of the Haute Cour to Nablus, a power base of the Ibelin family. Their goal was to place Isabella (Sibylla’s sister and Balian’s stepdaughter) on the throne, along with her husband, Humphrey IV of Toron. Most of the powerful barons attended. However, Sibylla was not without powerful support. Count Joscelin, as royal seneschal, occupied the city of Acre, which was part of the royal domain, and seized the Lordship of Beirut, which belonged to Count Raymond. Then Joscelin, Sibylla, and William of Montferrat accompanied young Baldwin’s coffin to Jerusalem. Upon their arrival, Guy garrisoned the city with his own forces. Sibylla found strong support in the city, including the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Heraclius; the royal Constable, Aimery de Lusignan (Guy’s brother); the royal chancellor and Bishop of Tripoli, Peter of Lydda; the most powerful noble in the Kingdom, Raynald de Chatillon, and the Master of the Temple, Fr. Gerard de Rideford. Civil war was brewing.

Raymond and Baldwin of Ibelin then sent a delegation to Jerusalem to dissuade the nobles there from crowning Sibylla. They reminded the nobles of an oath that the Haute Cour had sworn to Baldwin IV in 1183. To provide overwhelming support for the next monarch, they had promised that if young Baldwin V died before the age of ten, the regency would go to Raymond III of Tripoli, and any new monarch would require the approval of the Pope, the Holy Roman Emperor, the King of France, and the King of England. Sibylla’s supporters denounced the agreement, arguing that those powerful sovereigns were too far away. Immediate resolution was necessary. The nobles announced that Sibylla had the better claim, but they agreed to support her only if she put aside her detestable husband, Guy de Lusignan. She countered with two conditions of her own–that her daughters with Guy receive legitimacy and that she be allowed to choose her next husband. The Haute Cour agreed.

Coronation of Guy and Sibylla from The Kingdom of Heaven (2005); amidst great controversy, the two ascended the throne in Jerusalem in 1186

Sibylla then invited the nobles of Nablus to attend her coronation, but they refused, probably pressured by Raymond and Balian. With no time to lose, Sibylla’s supporters proceeded with the coronation plans. There was, however, the question of the royal regalia, which remained locked in a special treasury, opened with three special keys. The Latin Patriarch held one, and the two masters of the religious-military orders held the other two. Patriarch Heraclius and Templar Master Gerard de Ridefort supported Sibylla, but the Master of the Hospital, Roger de Moulins, an ally of Raymond and Balian, did not. However, Raynald de Chatillon, accompanied by Master Gerard de Ridefort and a troop of Templars, decided to press the issue for Sibylla. Joined by Patriarch Heraclius, they browbeat the Hospitaller Master. Realizing that he could not stop them without bloodshed, the disgusted Hospitaller Master threw the key out of a window but declared that neither he nor his brothers would have anything to do with the coronation. Unfazed, the Templars and Raynald escorted Sibylla to the Holy Sepulcher, where they crowned her Queen, probably in September. Then, she shocked her own supporters by reneging on her promise to put aside Guy. Instead, she crowned him as King of Jerusalem. The couple then granted additional lands to Count Joscelin. In turn, Joscelin arranged for marriage ties between his family and Guy’s. For his part, Raynald reclaimed his status as the principle lord of the Kingdom, his name appearing first on many royal charters from 1186 to 1187.23

Raymond’s and Baldwin’s attempted coup ended when Humphrey of Toron refused to take up arms against Guy, pledging his allegiance instead.24 A Muslim chronicler, Ali ibn al-Athir, stated that Raymond remained in a “state of open secession and rebellion” against Guy.25 Raymond departed the kingdom in disgust, returning to Tripoli. Baldwin of Ibelin then went into self-imposed exile, leaving the kingdom for Antioch because he refused to swear fealty to Guy. That left Balian as the new lord of Ibelin, and he reluctantly swore fealty. Balian also agreed to care for his nephew, Thomas, who did not accompany his father to Antioch.

Describing the Kingdom’s plight under the likes of Baldwin IV, young Baldwin V, Queen Sibylla, King Guy, and Count Raymond, the famous English historian, Edward Gibbon, dryly wrote, “Such were the guardians of the Holy City—a leper, a child, a woman, a coward, and a traitor: yet its fate was delayed by twelve years by some supplies from Europe, by the valour of the military orders, and by the distant or domestic avocations of their great enemy.” Strangely, Gibbon, perhaps limited by his sources at the time of his writing, is kind to Raynald and silent on Gerard. In any case, the Kingdom certainly hung by a thread in 1187, and the vacuum of leadership in Jerusalem soon proved fatal to the Crusader cause.

This is the end of Part I.

Part II will explain how war broke out between the Christians and Muslims, how Saladin crushed the Frankish host at Hattin in 1187, how the Christians defended Jerusalem that same year, and how most of the Kingdom fell in the following months—losses so shocking that they stirred the Third Crusade.

1: Sunni Islam is the majority sect of Islam, the minority sect being Shi’a. Members of the two sects traditionally loathe each other, considering each other heretics.

2: Edward Peters (ed.), The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press: 1998), 4.

3: The Byzantine Empire was the surviving eastern half of the Roman Empire. The Western half had collapsed in the fifth century, but the wealthier eastern half had remained relevant in the seven centuries since then. Yet, Muslim invasions had sapped its strength since the seventh century.

4: Edward Peters (ed.), The First Crusade, 17. Also Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume VII (London: The Folio Society, 1989), 254-255.

5: Mosul is a city on the Tigris River in northern Mesopotamia. Atabeg, a Turkish title of nobility, meant roughly ‘father-prince’. Several Turkish lords in Syria held this title (notably those in Mosul, Aleppo, and Damascus). In theory, the atabegs ruled as governors on behalf of the Seljuk sultan, at least until the Sultanate disintegrated after 1156.

6: Desmond Seward, The Monks of War (London: Penguin, 1995), 50. Gibbon also notes his piety. Gibbon, Decline and Fall, Vol. VII, 328.

7: Amalric is sometimes rendered Amalricus or Amaury. The son of King Fulk of Jerusalem and of Queen Melisande, he succeeded his older brother, Baldwin III.

8: Maria was the great grand-niece of the Byzantine Emperor, Manuel I Komnenos.

9: Miles was assassinated in Acre in October of 1174. No evidence points to Raymond, but he benefited most.

10: Outremer literally means ‘beyond the sea’, and thus the Franks used this term to indicate ‘the land beyond the sea’, meaning the Holy Land or the collection of Frankish crusader states there.

11: He is also known as Odo of St. Amand.

12: Desmond Seward, The Monks of War, 51.

13: From 1177 to 1180, Raynald’s signature appears on royal charters as the first among witnesses, signifying his importance as one of the king’s most important officials.

14: Barisan, the first Lord of Ibelin, had three sons—Hugh, Baldwin, and Balian (the same Balian that later took command of the defense of Jerusalem in 1187). Barisan had died in 1150 and Hugh died in 1169, leaving Baldwin as Lord of Ibelin. In 1177, Balian married Baldwin IV’s mother, the Dowager queen, Maria Komnenos, tightening the ties between Ibelin, Tripoli, and Constantinople.

15: Malcolm Barber, The Crusader States (Yale University Press, 2012), 209.

16: Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Volume II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 357.

17: Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Vol. II, 361 and 365.

18: Bernard Hamilton, The Leper King and His Heirs (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 117.

19: Hamilton, The Leper King and His Heirs, 170-171.

20: Stephen Howarth, The Knights Templar (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1982), 138-139. Also Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Vol. II, 437. Howarth gives the most detailed description of the affair.

21: The Lord of Botron was William Dorel, his daughter was Lucia, and the Pisan merchant was Plivain (sometimes given as Plivano or Pleban). The Estoire de Eracles relates a story that this merchant promised Raymond her weight in gold.

22: Joscelin was the brother Agnes of Courtney, the first wife of King Amalric of Jerusalem. He was also the Seneschal of the Kingdom from 1179 to 1190. The influential Courtney family was a lesser branch of the royal Capet family of France. Agnes had a vested interest in seeing Baldwin V, her grandson, thrive. Likewise, Joscelin was looking out for his great-nephew. They were both wary of the machinations of Maria Komnenos, the second wife of Balian of Ibelin, who wished her own daughter, Isabella, to rule.

23: Bernard Hamilton, “The Elephant of Christ: Raynald de Chatillon”, Studies in Church History (15), 1978, pages 107-108.

24: Remember that Humphrey was the stepson of Guy’s powerful ally, Raynald de Chatillon.

25: Francesco Gabrieli, Arab Historians of the Crusades (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1993), 114-115.