This is RPG-ology #86: Uncertainty, for January 2025.

Our thanks to Regis Pannier and the team at the Places to Go, People to Be French edition for locating a copy of this and a number of other lost Game Ideas Unlimited articles. This was originally Game Ideas Unlimited: Uncertainty, and is reposted here with minor editing [bracketed].

As somewhere in the back of my mind I considered recent entries in this series, I realized that there was a connection between one of the ideas in Wizardry and one of those in Tactics. It has to do with an aspect of strategy which is very important in any conflict, one on which I have often commented in other contexts; and although these two articles touch opposite facets of that aspect, they are really about the same thing.

The first step toward winning any conflict is assessing the opponent’s strength. Games are won and lost entirely on mistaking the opponent’s abilities. High school sports teams today employ people to observe the other teams at practice and in play, even to video tape them, so they can examine who are the good players and what are the team’s strengths. If you fail to assess the opponent, you might still win, but your chances have been reduced significantly.

But I’m not today writing a piece on how to assess the strengths of your opponent in role playing games. Given the variety of such games, that would be a daunting task–weapons skill, magical abilities, mental powers, strategic planning, technology, and terrain are all just the beginning of such an evaluation, and any of them could be totally absent from a particular[ly] game. If I’ve called your attention to an aspect of combat strategy you had not considered, it’s something to explore; and perhaps I will explore it in more depth another time. But today we’re going to look at this from another angle.

In Back to the Future, at the critical moment, Biff Tannen is wrestling with George McFly and trying to force himself on Lorraine at the same time. George is no match for Biff; he could no more beat Biff in a fair fight than I could wrestle Andre the Giant into submission. He knows it; Biff knows it. But Biff’s problem is that he does know that. He doesn’t consider George a serious threat. In fact, he’s restraining him with one hand while he uses the other to accost Lorraine. And that is his mistake. George flattens him with one well placed punch. He may not be able to take Biff down in a refereed boxing ring, but he’s not entirely helpless, either. Biff has underestimated him, and in that moment when the monster is distracted, George strikes.

In a similar vein, many of my characters have kept a hole card, an ability that they could use in an emergency to turn the tide. It’s usually something which could only be used once–a magic scroll, a potent explosive device. I tend to refer to it as my insurance. I don’t always know how, or even if, it will work, but I know it’s there if I need it. Since it is never revealed until desperately needed, its use is always unexpected.

The lesson is that you can defeat even a superior opponent if you can convince him that you are less of a threat than you are. If your adversary believes he need not waste effort on you, you have one chance to defeat him.

But that’s only one side of the idea. The other side is equally valuable.

My kensai character was a man of no little pride. He would in introducing himself recite his name and family, his titles, his family alliances, all in a matter-of-fact tone that was in no way demeaning or challenging but was exactly who he understood himself to be. He took his people on dangerous missions into places from which people were not expected to return. On those roads, if you encountered anyone, they were certain to be strong, well-armed, and ready to fight. But fighting exhausts resources. It depletes ammunition, injures fighters, spends magic, and demands medicine. Anyone who was not part of his purpose was not, in his mind, an enemy. Thus when those encounters invariably arose he began by introducing himself, and then making a rather simple statement: I have no quarrel with you; however, if you insist on fighting I am quite prepared to kill you. You don’t want that, I’m sure. So if you would like to stay alive, we don’t have to fight. Was I always certain that my people could defeat everyone we encountered? I was never certain. Did I think my character had such bravado? No, he was not like that. But we rarely had to fight any intelligent creatures. My apparent confidence in our ability was sufficient to persuade them that attacking was foolish.

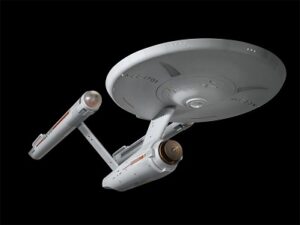

There are other ways to do this. In an old Star Trek episode, at the moment at which it appears The Enterprise has been outmatched and outmaneuvered, Kirk tells Spock that the game is not chess but poker. He promptly informs the alien adversary that the ship is equipped with a Corbomite Device, such that if the ship is destroyed everything in the entire sector will be destroyed with it. The bluff works–not perfectly, but sufficiently to keep the attack at bay while the problem is considered in more detail. When in our earlier article the wizard faced Axelrod, he used the little tricks that he did know to create the illusion that he was much more powerful an adversary than the fighter wished to confront. If you can convince your opponent that you are more dangerous than you are, you might not have to prove it.

The concept is to mislead your enemy in his efforts to assess your strengths. If he thinks you are more or less powerful than you really are, you can use that to your advantage. There’s a reason poker is played with hidden cards; it prevents anyone at the table from being entirely certain of the outcome. That uncertainty is the edge you seek. Whether you get it from Battle Plan Three, convincing the enemy that he has already won so you can rise up and strike by surprise, or by sheer bravado, conveying the notion that you are unassailable, it gives you an advantage in any conflict.

This all requires something from the referee; and not every referee will be able to handle this kind of play–particularly if he has not considered it. The referee is always in the rather awkward position of having to play antagonists from what they know, not from what he knows. Assessing whether you have indeed misled your nemesis or have not outsmarted him this time is not an easy challenge. But the fair and capable referee should be able to rise to it.

Next week, something different.

In systems which rely heavily on dice rolls for this type of interaction successful bluff/diplomacy/whatever in your system roll could suffice to determine the antagonists fall for it or not.

Personally, I like deciding myself as a GM. Maybe influenced by a die roll to determine how deeply the antagonist is ensnared, or how vigorously he pursues. But GMs shouldn’t let bad, or good, dice rolls get in the way of good play by the PCs, nor waste a chance for a good story.

Indeed, there are two sides to that.

On the one hand, if the dice are going to make the decision, what’s the point of having the player struggle through it?

On the other hand, if the character’s stats make him particularly persuasive or charismatic, why should his effort stand or fall on the possibly less impressive skills of the player?

I’ll usually go with the dice, modified by the player’s performance, depending on whether the character stats strike me as considerably higher (or lower) than those of the player.

I often like to have the player roll as soon as it looks like they intend to make a social check, then do the roleplaying afterward. That way everyone knows whether the bluff was successful or not, and they can modify their roleplay appropriately. It’s much the same as a combat roll: declare intent, make the roll, then narrate the outcome.