This is RPG-ology #30: Story-based Mapping, for May 2020.

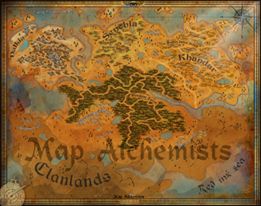

I have mentioned before that I belong to a role playing game mapping group on Facebook. Every day people post beautiful world maps similar to the ones pictured here and ask for feedback.

I am not a cartographer; I am not an artist. When aspiring young artists send their work to me for my opinion I send it to my art director, because my opinion isn’t worth the price of a cup of coffee on free coffee day. If they want to know whether it’s beautiful, well, as I often say, a thing of beauty was made by someone else, and they look nice enough to me. If they want to know if the maps make sense geologically and geographically, I can point out problems (such as those we’ve covered in previous RPG-ology articles including #5: Country Roads, #10: Labyrinths, #13: Cities, and #18: Waterways).

But if they want to know if the maps are useful, it always makes me feel like that’s not really a good question. I can’t imagine ever having a use for them—but it took me a while to understand why.

Map by Steve Gaudreau

When I start a map, I begin with the question, Where are my characters right now? Unless I have a good reason to think otherwise, that is the middle of the piece of paper that’s going to be my map. (Even when I make maps on a computer I generally have a “virtual piece of paper”, boundaries of the image file and a graph paper grid covering most of it.) This probably includes a vague notion of Where is the rest of the world?, but as Max Smart once said, “I’m not saying that the rest of the world isn’t lost, 99.” I need a vague notion of how the characters got here which contains some information about the rest of the world, but since they’re not going to live that part in the story I don’t really need details.

What I do need is the answer to two essential questions. The first is What is around them that they are going to want to examine? If they are in a village, I need an inn, stables, tradesmen and craftsmen, probably a constabulary, homes of those who live in town, and probably at least one place of worship. If it’s a city, I’ve given myself a lot more work, because there are a lot of places someone can go in a city. In most cases I don’t really have to know how far it is from London to Paris, but I do need to know how far it is from the rooming house to the grocery store.

Map of Kaiden by Michael Tumey

The second question is Where are they likely to go from here? Not Paris, we hope, or at least not yet. The first place they’re likely to go is whatever place I have planned for them to have their first adventure. That might be a dungeon, or a ruin, or an office building, or a spaceship, but whatever it is, I now have to expand my maps to show how to get from here to there, and what they will find when they get there.

There will be other places where they will go. If they acquire valuable objects, whether jewelry or magic items or tapestries or computers, they probably need to take them somewhere to sell. That means I need a place where people buy such things, and I need to map the road between here and there and treat that place much as the starting point, creating what they are likely to see when they arrive. But I didn’t need any of that when the story started; I only needed to have a vague notion of where it was and what was there, so I could put the time into creating the map later.

I’ve called this Story-based Mapping because it is fundamentally about creating the world to meet the needs of the story. I’ll give kudos to Seth Ben-Ezra’s Legends of Alyria for using this concept. His world, Alyria, has a handful of significant landmarks—a major city, a huge library, that sort of thing. When the game starts no one has given a thought to where they are, and there is no map. When someone says they want to go to one of these places, the plot and the dice dictate how far it is, how difficult it will be to get there, and from that point forward we know where that particular landmark is relative to where we started. In fact, we might have established where two such landmarks are relative to our starting point but not yet know where they are relative to each other—the plot may at some point dictate that they are adjacent to each other, or that they are miles apart in opposite directions, or that there is an impassible mountain range or waterway or chasm separating them.

This is why those huge world maps don’t interest me. When I’m running a game or writing a story I need the map to form to what I’m writing. If I already have a complete map of the world and suddenly I need a pirate base somewhere near my port city, I have to scour the map to find an appropriate location for such a base. If I’m working with a story-based map, I simply have to expand the map to include the cove or island or port that provides my pirates with a safe haven, and it can be perfect for their needs and pretty much anywhere I want it to be that the characters have not already investigated.

I don’t think those huge maps are useless. If you are creating a world for other people to use in their games, such as Krynn for the Dragonlance Adventures, having a map that shows where all the countries are located will help those other people run games in them. But I think that something like the map of Middle Earth, while it might have been drawn from Tolkien’s mind before he started writing, arose organically from the story he wanted to tell: I need hobbits to start in a quiet remote part of the world and travel a very long way through a lot of dangers but also a few safe spots and ultimately reach a distant dangerous place where they can destroy the Maguffin. Let’s outline what those dangerous and safe places are and where they are located, and then we can create the story to connect the dots. So if I know what the entire story is before I start writing, I can create the entire map to fit it—but I never know the whole story, not when I’m writing it and certainly not when I’m “playing bass” for a bunch of players who are going to create the story. I need to be able to create the world as the story needs it, not be locked into land masses and cities and waterways that were created in the hope that they would make a good place for a story.

I’ll probably be thrown out of the RPG Mapping group for this, but I hope it helps some of you understand how to approach making useful maps for your adventures.

Thanks to artist cartographers Steve Gaudreau of Map Alchemists and Michael Tumey for the use of their world maps.

Previous article: Political Correction.

Next article: Screen Wrap.