Guy Sclanders, host of How to be Great GM,

provides exceptional tutorial videos online

After DMing for many years, I started watching videos online about creating campaigns and adventures. Many talented people have put out interesting content in recent years. Having a bit of experience, I find some online personalities more helpful than others (Guy Sclanders from Great GM is my favorite). I’m now trying to internalize some of the new tips that I’ve gleaned, but this is easier said than done. Understanding what someone says in a video is not the same as knowing how to do it instinctively. Writing notes for myself usually helps me to grasp a concept better, but the best way for me to internalize something is to use it. Well, I found all of these videos just as I was planning to design my very first online adventure (which I want to be short). I want to incorporate these new tips while making this new adventure, recording my thoughts along the way. It will be a good reference for me afterwards.

At the moment, I have nothing done. I shall design this adventure as I work through the steps below. Talented DMs like Guy Sclanders can do this with amazing speed and with minimal notes. Alas, that is not my strength. I need to see things in writing, and I like to take my time. If you think the process below may be helpful to your own game in any way, read along with me. If you really want a challenge, join me by designing your own short adventure as you read through the steps below.

Step 1: Decide on a Genre/Setting

It makes sense to tackle this before worrying about small details. What sort of game do you want to play?

The members of our online group recently decided that we were pretty bored with the typical European High Middle Ages setting and atmosphere. We opted instead to lean towards more of a sword & sorcery, Conan the Barbarian, Beastmaster, Red Sonja, Dark Ages feel. In our online group, we are rotating DMs for various reasons. Not all of our DMs are purists when it comes to setting, so orcs and such may appear, but we shall lean in the direction of sword & sorcery when we can. With this adventure, I hope to lead the way for the group, capturing the feeling of the sword & sorcery genre.

Step 2. Consider Themes and Motifs

This is an advanced tip, but I think that it greatly enriches your work with only a little effort.

An adventure can contain all the obvious requirements of a fun game (interesting monsters, treasures, traps, puzzles, etc.) but still feel mediocre because it lacks atmosphere or flavor. Sometimes, the root problem is not blandness in the details, but randomness. Imagine a party encountering unicorns and pixies in one town and Lovecraftian horrors in a neighboring town. Alternatively, envision several encounters that feature slapstick comedy while other encounters in the same adventure focus on brutal oppression. This sort of jumble often produces an unsatisfying mood that confuses the players. Deciding beforehand on the rough feel that you want your adventure to have will solve this problem.

If you’ve forgotten what themes and motifs are, here’s the briefest refresher (I’m married to an English teacher so I’d better get this right). A theme is just a dominant idea that pervades the story. There can be more than one. A motif is just a repeating image or symbol that reinforces a story’s theme. Put differently, motifs are the things that we would expect to see in a story about a certain theme. For example, Prince Charming, a fairy godmother, spells, and a witch are all motifs that support a fairytale theme. Together, these literary elements should bring flavor and consistency to our work.

We’ll worry later about HOW to include themes and motifs. For now, just think of which ones you might want to include. In this adventure, I’m thinking of a theme of power and corruption. The idea that power corrupts, though fairly common, is always relevant. In this adventure, I’d like to depict the world as brutal and dark, with the few scattered towns being sinkholes of vice, brutality, and corruption. Against such a backdrop, PCs could really seem like heroes (though possibly short-lived ones). Motifs for a theme of power and corruption might include titles/honors, lions, dragons, crowns, rods, coins, and lightning bolts, as well as a serpent, an apple, bribery attempts, thirty silver coins, disease, decay, dead animals, rotting food, mold, moth eaten cloth, prostitutes, temptation, difficult choices, grumbling minions, and rebellion.

Step 3. Consider Expectations of Above

Honestly, I’ve never really taken this step before. The goal here is to think about what our choices thus far should mean. How will they manifest in our adventure, if we are successful? Players come to your game with certain expectations. You do not want to disappoint them. This does not mean that you cannot have surprises, but the surprises should not radically depart from the expectations, lest the players walk away disappointed. If they are yearning for sword & sorcery and you give them a space comedy, it probably won’t matter how good your space comedy is. They will likely feel disappointed.

What does the sword & sorcery genre mean for this adventure?

Civilization will be limited to a few scattered cities with large tracts of wilderness in between. Those cities or towns shall be ancient, corrupt, and weak by common standards. The home base of the PCs is a large port city, at least large by standards of the day (I’ll just call it ‘the city’ hereafter). As for the wilderness, I want it to have the feel of the Near East. There are beautiful mountains and stretches of forest, but many areas are dusty, dry, and rocky. There is no lush, green land like medieval England, France, or Germany.

Sidenote: I am not designing a world, for we are using a map that a friend drew up. Much of it is blank, so I’ll just need to choose a spot on the map for this adventure. The notes on civilization above will guide me when developing small locales, like villages and such.

Military technology will be limited, with only the greatest and wealthiest warriors clad in chainmail (including the PCs). Platemail is almost non-existent. Most warriors wear scale, studded leather, or ringmail. Though I will not limit PCs, most archers will use shortbows. I will avoid crossbows. If I make magic weapons, I’ll ensure that they fit this genre.

Polytheism is the norm, and no single church wields tremendous influence (there is nothing like the Roman Catholic Church of the Middle Ages). There shall be clerics, but they may appear weaker than those in most standard fantasy games. The gods may exist, but they shall appear more distant. Again, I won’t limit the PCs (the current party only has one cleric, and she’s a bizarre cleric of Kord), but featured spells will place less emphasis on flashy magic and more on subtle aid.

As for monsters, the players likely expect savages, raiders, brigands, slavers, wizards, demons, man-apes, reptile men, limited undead, perhaps dinosaurs, etc. I’ll try to avoid the common monsters from Greek myth. I’ll also avoid many fay creatures (at least how they are commonly presented), as they usually give off a much lighter tone.

Last of all, the sword & sorcery genre features action. Our adventure should have plenty of combat. It need not be a slugfest, but it should not be a slow-paced mystery.

What do my theme and motifs mean for this adventure? These are all negative (corruption, vice, brutality, etc.). I want players to feel like they would be very uncomfortable living in this setting. Trustworthy friends are rare. Respectable institutions are almost non-existent. Lawful authorities are weak outside

the few cities, and justice is fleeting, which results in endless violence. Without a strong religion or philosophy to provide moral foundations, decadence is common. Wealth is tough to attain so people often lie, cheat, steal, and kill for it.

The theme of corruption will certainly influence the way that I write my NPCs! By the way, this doesn’t mean that I cannot feature a good NPC or a good NPC organization. I plan to do so, but they will be rare and will seem especially good compared to everyone else. Most NPCs will be self-serving. Many will be violent. This may change even basic encounters. Although I have no encounters planned yet, I can give a possible example here. I like to start my adventures with combat, just to get the excitement level up. The initial battle often has little to do with the main plot. If, for example, I had the PCs defending a caravan against brigands, my theme might actually change this simple encounter. Instead of a straight-forward battle, with PCs and other low-level caravan guards fighting off brigands, I may have the leader of the caravan guards join the brigands (perhaps he is even their leader). That actually sounds good, so I’ll put that on a shelf for now. You get the idea.

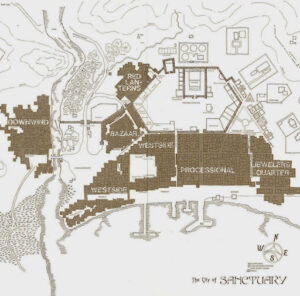

The City of Sanctuary from the Thieves World series, created by Robert Lynn Asprin in 1978

Perhaps the theme will also influence location descriptions. A city that is corrupt and decadent will look and feel very different than one that is well-run. Compare Ed Greenwood’s city of Waterdeep from The Forgotten Realms with the city of Sanctuary from Thieves’ World. The former seems like a nice place to live. The city is clean and orderly, its powerful Lords provide both justice and order, and multiple temples serve the city and the poor. In contrast, Sanctuary is a cesspit. The ruler is largely aloof, most officials are corrupt, and the Hellhounds (the ruler’s enforcers) brutally maintain order, caring little for justice. I would never wish to live there. Yet, given a choice of where to set an adventure, I’d pick Sanctuary over Waterdeep any day of the week. In this adventure, my theme means that any settlements will be seedy and unwholesome places, where PCs must be on their guard (not the best places to rest).

Even outcomes may become darker because of the theme. For example, if the PCs are seeking some missing NPCs, perhaps they will not find them alive and well. The PCs may find that some are dead and the rest have been sold into slavery.

Just from writing the above, I am definitely in a different frame of mind. This should help as I create the adventure. Even better, if my planning spans several days (very typical), I can re-read these notes each time to put myself back in the proper frame of mind.

Step 4. Consider Player Styles and Interests

To maximize player fun, a good DM should always consider the players’ preferred styles and interests. You can plan a great murder mystery, but if your players hate mysteries and love to kill everything in sight, the adventure will probably be a disaster. As a rule, larger groups are usually more difficult to satisfy because the chances are higher for players having very different styles and interests.

For this short adventure, I will have some difficulty because our online group is rather large (six to ten players), and the players have wildly different preferences. At least I know that at the start. Some of the players love combat to the point that they seem to get restless if they are not throwing dice after 20 minutes. Fortunately, the sword & sorcery genre calls for action, so this should not be a problem. I am unsure about three specific things–politics, puzzles/riddles, and traps. Players often love or hate them. I want to see if our group has any consensus on these features. If so, it will make design easier. I assume that there will be little consensus, but you never know. I shall poll my players (via text or email or Discord) with three quick questions.

Step 5. Choose a Game System

Game mechanics matter, for they generally influence player behavior (and thus PC behavior). The mechanics will directly affect how your game unfolds. Simply put, some game systems handle specific genres better than others. For example, Dungeons & Dragons does not do horror as well as The Call of Cthulhu. With enough tweaking, you can make anything work, but choosing the best system may save you lots of work. Of course, if you don’t have many game systems or if your players don’t want to experiment with various systems, then simply go with what you know.

In our case, the group already decided on Dungeons & Dragons 3.5 at the onset. This will work well enough for sword & sorcery, as that genre heavily influenced Gygax and Arneson when they created D&D. I will not limit the PCs in any way, but to create the mood that I’m seeking, I will be picky in what monsters and what spells I feature in the adventure (more on that below).

Step 6. Decide Between Sandbox and Plot

I usually associate this question with campaigns, but it applies to adventure design too. For any that are unfamiliar with the term, sandbox refers to a detailed setting that PCs are free to explore at their leisure. There is no specified plot, quest, or mission. DMs have had a longstanding debate on whether DMs should ever create a plot, and there is no correct stance. I find that my vocabulary has evolved, even if my stance has not. I used to argue that the DM should not write plots, arguing that this was the players’ collective job. I have since amended my terms. The DM should indeed write a rough plot, based on the universal template of ‘someone wants something badly and is having trouble getting it’. However, the DM must not script the story, as this is the job of the players. The story is HOW the PCs interact with the plot and the rest of the setting. The story is what eventually happens during the session. If a DM takes over that role, the players are relegated to audience members. In any case, a DM’s choice of sandbox or plot greatly affects adventure design.

I currently want to practice making my adventures more story-like, which requires creating clearer plots. It’s really a matter of pacing (more on that later). Thus, for this adventure, I shall prepare a rough plot. It will not be a sandbox (I want to play with that at another time).

Step 7. Brainstorm Components

In one of his online videos, Guy Sclanders suggested filling in a simple 5 x 5 table before you start making choices for your adventure. The headings of the table are basic elements that you’ll want during adventure design. He suggests brainstorming five options for each heading. Don’t worry too much about making them unique or perfect (you can tweak them later). When writing the options, try to remember your self-imposed limits, based on your chosen genre, theme, and player styles/interests. The purpose of making this table is to provide you with a bucket of possibilities during the design process. Later, when you find that you need a monster, you can look at this short list rather than poring through all the monster books again. Likewise, when you need a trap, magic item, or location, you can quickly reference these lists.

I sometimes ask my players what specific magic items they would eventually love for their PCs to obtain. I don’t give them everything they want (and certainly not in one adventure). Yet, having this wish list can improve your game. Your players may appreciate that you are customizing the adventure for them. Moreover, there may be times when you are just stuck, and their wish list will help. It may arise that you need to place a minor magic item in a treasure horde but have no strong feelings on what it should be. Check the PCs’ master wish list and grab anything that suits the adventure.

Likewise, I have occasionally asked players what monsters they would love to face. I will not insert a requested monster that does not fit the genre, but I can usually find a few requests that do, or I can tweak one of their requests until it does. In another adventure that I’m planning, I noticed that a player had earlier asked to encounter a satyr. The typical satyr didn’t fit what I was doing, but by tweaking his idea I unwittingly created my main monster for that adventure (a satyr-looking demon).

For this adventure, let’s try to fill in the five headings, as follows:

George Lucas used three radically different environments to great effect in The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

Potential Locations

This does not require much explanation. Yet, I will add a suggestion here, based on the practice of George Lucas, who purposely featured three very different environments in each of his three original Star Wars films. Each environment gives off a very different feel, and variety is nice. Also, even in a two-hour movie, the drastic change in environment makes the saga seem longer, more far-reaching, and thus more epic.

In fantasy gaming, dungeons are fairly common. As a dungeon can exist beneath almost any environment (forest, tundra, jungle, farmland, etc.), it is very easy to get two very different environments for an adventure. Just try for a third type. If you are stuck, or if a radically different setting will not suit your adventure, realize that you can vary underground settings enough to make them feel like two very different environments. For example, wandering through the cavernous halls of a dwarven king would feel very different than the extremely tight, claustrophobic tunnels of a catacomb. Likewise, spacious natural caverns, perhaps magically lit or illuminated by phosphorescent lichen, will feel very different than the foul sewer system of a large city.

I know that sword & sorcery adventures are set in almost every type of environment. Yet, for this adventure, I do want to emphasize a dusty, rocky, hot environment, reminiscent of the Near East, as this rarely features in our games. I want at least one scene set on a rocky plain. An underground crypt or temple would contrast well with that. What else? Looking for books for my young daughter, I recently skimmed a ‘choose your own adventure’ book by James Ward called Conan the Undaunted, and part of the story featured haunted ruins. Ruins fit perfectly with the genre, so we’ll include them here. To contrast with dry and dusty, let’s also feature water. Perhaps the PCs must cross a lake, perhaps on a boat. Last of all, let’s get some height. Let’s use an old crumbling tower. Thus, for this adventure, we’ll start with:

(1) Rocky and parched plains (outdoors)

(2) Underground crypt/temple (indoors)

(3) Haunted ruins of an ancient city (outdoors)

(4) Tropical island on a mist-shrouded lake (outdoors)

(5) Crumbling stone tower (indoors)

Potential PC Deaths

Guy Scalanders explained that these are not ways that you plan to kill the PCs. Instead, these are exciting dangers that you can add to the adventure. So, after seeing an entry entitled ‘falling off a cliff’, you can set a battle on the edge of some very high cliffs. This at least allows for several exciting possibilities, such as a PC wrestling with a monster on the edge of the cliff, a PC throwing or knocking a monster off the cliff, a PC falling over the side and clinging to a dead tree root, etc. For this adventure, we’ll start with:

(1) Falling off a 1000’-high cliff

(2) Eaten by a monster

(3) Crushed by a large inanimate object

(4) Killed in a cave-in

(5) Burned alive in a conflagration

Darel Greene’s cover painting for Conan the Swordsman (1978) by L. Sprague, L. Carter, and B. Nyberg

Potential Traps/Hazards

I do think that most adventures should have some dangerous challenges that cannot be overcome with a sword or by negotiation. Yet, my short survey (given since I wrote Step 4) showed that few of the players love traditional traps. Thus, I’ll brainstorm more hazards than traps. If any idea seems like a traditional trap, I’ll ensure that it does not produce immediate death or damage (a reason why many players dislike spiked pits, poisoned needles, etc.).

Part of Dave Trampier’s painting for the cover of the original Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Players Handbook (1978)

Thinking back on various sword & sorcery films, water came to mind first. Perhaps the PCs must dive beneath some water to get somewhere or to escape something. Water threatens PCs with drowning and also hides potential monsters. How about a room or area that fills with water? Having included water, let’s use fire for contrast. Perhaps a wall of fire (magical or otherwise) prevents access to something. My mind then jumped to the lava pit inside the Thuggee temple in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. I don’t really want lava here, but perhaps hot coals will do. Perhaps there are braziers filled with coals, or perhaps there is a pit filled with them. What else? Falling is always scary, and we mentioned cliffs above. Perhaps the PCs will need to scale some steep cliffs. Ok, we need one more. My mind went to Conan the Destroyer (1984), when Conan had to lift a solid stone door. Perhaps we can use something like that. Thus, for this adventure, we’ll start with:

(1) Room filling with water (or a water barrier)

(2) Wall of fire

(3) Pit filled with hot coals

(4) Steep rocky cliff

(5) Stone wall or door descending

Potential Monsters

Personally, I find monsters to be a key part of the design process. I tend to prefer my adventures (and campaign worlds) to be a bit more homogenous than most. I dislike having dozens of different fantasy races mingling together. It simply doesn’t appeal to me, probably because it’s so fantastic that I cannot relate it to any literary works that inspired me to play in the first place. Given my finicky tastes, I will be a touch more careful here than you might be when creating your own adventure. If orcs, githyanki, pixies, mummies, and mermen all fit perfectly in your campaign, then go for it.

I will be a touch stereotypical with monsters, looking to capture the flavor of a sword & sorcery adventure. At some point, Conan always cuts down a dozen human warriors in crappy armor. We need some of them. Ok, what else? A novel on my night table, entitled Conan the Swordsman, has a cool cover with some sort of flying dinosaur. That’s unusual and gives me a flying monster. Since I mentioned haunted ruins above, perhaps we can use some ghouls skulking around the ruins at night. I like that, and it gives me some undead. This will be especially interesting since the party has only one very non-traditional cleric. My eyes then fell upon the cover of the original Players Handbook. I’ve wanted to use a temple setting like that for a long time. Perhaps we’ll throw in some lizardmen or serpentmen. They’re interesting and different. I need one more option. I am tempted to throw in a wizard or sorcerer, but it takes time to do them any justice. Another adventure that I’m planning for the same group focuses on a wizard, so I’ll avoid one here. Maybe I’ll add an incorporeal monster, something that they cannot pummel or shoot to death. Perhaps a ghost, wraith, or specter would fit well with haunted ruins. Thus, for this adventure, we’ll start with:

(1) Human brigands or guards

(2) Flying dinosaur lizards (giant pteranodons?)

(3) Ghouls

(4) Lizardmen or snakemen

(5) Incorporeal undead

Potential Magic Items

I approach this from different angles. Most important to me is ‘What magic items are important to the story?’. If the heroes will need a special dagger to defeat the

monster, then that special dagger needs to be on this list. If there is an item that you wish to introduce for future adventures, it should be on the list. Next, I consider whether there are items that I really like and want to include, perhaps because they work well with the adventure’s genre. Last, I look to see if any item on the PC’s master wish list would fit with the adventure.

My priestesses of Palladine Mithrallas are inspired by the unnamed warrior-priestesses in Red Sonja (1985)

For this adventure, the only item that I knew from the start that I wanted to introduce was a sunsword, kept by a high priestess that I developed for another adventure (set in the same campaign world). I have no idea what role my priestesses of Palladine Mithrallas may play in this adventure, but I would like to unveil that blade somehow. What else? I envision sword & sorcery magic to be subtle, so perhaps a gem that allows the possessor to have some form of clairvoyance (much like a crystal ball). Perhaps a wizard’s or priest’s enchanted skullcap helps him to focus, providing him with bonuses to spells. Somewhere above, I mentioned snakemen. Perhaps an amulet provides some bonus against venom or simply prevents attacks by serpents. Somewhere above, I mentioned slaves. Perhaps an enchanted iron slave collar makes the wearer submissive (unable to attack). That last one is sort of strange, so perhaps I should come up with a backup item, just in case. Perhaps a magical scroll contains a unique wizard spell that allows the caster to attack an enemy with unseen forces, much like Galdalf and Saruman used as they fought each other in Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring (2001). They were using their staves to do this, so it could also be a staff with this power. Thus, in this adventure, we’ll start with:

(1) Sunsword of Mithrallas

(2) Gem of clairvoyance

(3) Skullcap of focus

(4) Amulet against venom

(5) Collar of submission

(6) Scroll/staff of unseen forces (unique spell?)

Step 8. Consider Master Plot/Adventure Type

The master plot of a campaign is the overarching plot to which most other plotlines should connect. The villain wants something badly and is having trouble getting it (the PCs becoming the main source of trouble). Having a clear master plot makes creating adventures terribly easy. They almost write themselves. As events unfold over the course of several sessions, the villain often sets new plans in motion, creating adventure hooks. The DM trick here is to pay attention to the developments, thinking like the villain.

In any case, my current online group has no unifying master plot. This makes it somewhat lacking compared to other campaigns. I’m not sure if this makes my life easier or more difficult during adventure design. I need not worry about connecting the adventure to a master plot. Yet, a master plot usually makes it easier to come up with the adventure plot. Oh well. There is no master plot.

We should now stop to consider the general type of adventure that we want to run. In the past, I often thought of possibilities like ‘save the princess’, ‘kill the monster’, and ‘get the treasure’. These classification can work, but they are also limited. Guy Sclanders suggested four adventure types that subsume mine:

Thwarting Adventures, which can include ‘kill the monster’, require PCs to stop something or someone, perhaps by killing it/him, perhaps by destroying it, or perhaps by ruining its/his plans.

Collecting Adventures, which can include ‘get the treasure’, require the PCs to journey somewhere to obtain something that is ostensibly difficult to get. The journey home can be exciting or unimportant.

Delivering Adventures require the PCs to take something that they already have and bring it somewhere safely. The journey is key in such adventures.

Discovery Adventures require the PCs to explore an area or investigate a problem. The journey to the area may be significant, but the journey home is often not.

For this adventure, I have no strong preference. I think I may want to have the PCs try to retrieve that magical sunsword for the priestesses. This would be a collecting adventure. We’ll go with that for now.

Step 9. Create a Working Title

A good name is not terribly important, but I do find it useful. It focuses my thoughts and efforts. I usually end up changing the name several times. Just come up with something to start. My first thought here was simply ‘Into the Parched Hills’, for I thought I would set the small adventure there. I came to dislike that because it was too broad, saying nothing of the adventure itself. I changed it to ‘Light in the Darkness’, thinking that perhaps my sunsword would play a big part, perhaps hidden in dark, haunted ruins. That was better, but I still thought it too generic. ‘Light in the Darkness’ can refer to so many things. I wanted something that hinted at the setting’s flavor. I came to think I was closer with ‘Into the Parched Hills’, but I wanted to focus more on the haunted ruins. I needed a good name.

This derailed me for a bit. I looked online, skimming names of cities in ancient Canaan (Phoenician cities, Philistine cities, Hebrew cities, Moabite cities, etc.). Nothing jumped out at me. I looked at Hittite cities in Anatolia. Nothing. I then moved to Babylonian, Assyrian, and Sumerian cities in Mesopotamia. Frustrated, I then changed tack and looked at cities in Hyboria (the world of Conan). I still had nothing, though Conan’s archenemy, Thoth Ammon, kept popping into my head. At some point, I combined the city of Ur in Mesopotamia with Thoth Ammon, yielding the city of Ur-Ammon. Some scholars maintain that the Sumerian word ‘uru’ meant city, while the Hebrew word ‘ur’ means light or flame. I like the ancient images that these conjure. The name certainly doesn’t suggest Medieval Europe, and equally important, it doesn’t strongly suggest any popular earthly culture. I wanted to avoid names as suggestive as Hamunaptra (the fictional Egyptian city in the 1999 Mummy movie) or Zakhara (the pseudo Arabian land in Forgotten Realms). Thus, I recently settled on ‘The Ruins of Ur-Ammon’. I like it, but if I need to change it later, I will.

Step 10. Envision the End

To this point, I have only a jumble of cool components and the vague idea that the PCs will eventually try to get something. Before I worry about even the beginnings of a plot, I want to envision the climax of the adventure. It should be exciting, dramatic, and cinematic. It will likely be the best part. If you don’t love it, your players probably won’t, and they’ll likely care even less for the rest. The climax is worth some serious thought.

So how do we envision that climax? Guy Sclanders has an interesting method. With his 5 x 5 table, he writes out many combinations and does some free association to see what possibilities jump out. This may work for you. I have issues, however, and would feel compelled to look at all 120 combinations (did I do the math correctly?). For me, it is far easier to focus on the monster.

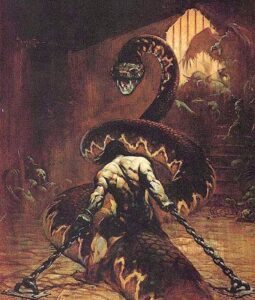

Conan faces a giant snake in Frank Frazetta’s Conan Chained, the cover of Conan the Usurper (1967)

How can I narrow this down further? For what it’s worth, I imagine the dinosaurs as obstacles along the way, not the final challenge. I’m not sure why. My first reason has to do with lack of intelligence, and this sent me down an hour-long rabbit hole. I pondered whether I should first nail down the villain’s goal/plan (see Step 11 below) before trying to envision the ending. I’ll spare you the details of my exhausting mental debate and simply write that I think we can envision the end first. Quite simply, what do we want the end to look like? We don’t need to know the how and the why yet. Getting back to the dinosaurs, it doesn’t matter if they are smart enough to be my final villains/monsters. The question is ‘Will they make for the coolest final battle?’ I say no. What about the specter or incorporeal undead? I have no logical objection. The snakemen simply appeal to me more for a final battle. Ok. Done! The PCs will fight snakemen. For now, forget about why or how.

Next let’s nail down the battle’s setting. I now look at the list of locations that we made earlier. The PCs could fight the snakemen amidst ancient ruins, but for some reason I imagine this final battle to be underground. Our crypt or temple would work well. Ok. So the PCs are fighting snakemen in an underground temple (maybe I’ll finally get a scene like that on the cover of the Players Handbook!). Well, this is interesting, but it’s still not exciting. Let’s make it dynamic by adding some danger.

Next, turn to the list of potential PC deaths. If the PCs are underground, they cannot fall off a cliff, unless there is a bottomless chasm in the temple. As for the danger of being eaten, I don’t think the roughly human-sized snakemen can swallow the PCs, but what if they have a giant serpent as a pet? That could be picturesque, with a tremendous serpent wrapping a PC in its tail while trying to swallow another. That has potential. Alternatively, if the temple roof is unstable (it is old, after all), a cave-in might be a real possibility. Perhaps the ceiling starts to crumble during the battle, and giant chunks of rock start falling randomly during the battle, crushing those that they strike. That seems to cover two options at once (cave-in and being crushed). What’s left? Perhaps the PCs are fighting the snakemen in the underground temple while it goes up in flames. Perhaps someone upends a large brazier during the battle, spilling hot coals that start a fire. This too has potential, though I cannot imagine too many flammables in a long-abandoned, ancient, underground temple. Maybe we’ll scratch that one. Of the above options, I like the fissure, the giant snake, and the collapsing ceiling. Having too many cool options is a good problem to have.

Can I use more than one in a given encounter? I believe that the purpose of the lists (or Guy’s original 5 x 5 table) is to provide each combat encounter in the adventure with a cool monster, a cool location, and a dynamic feature that makes it dangerous and exciting. Having five of each item suggests that you use only one dynamic feature (a collapsing ceiling, an inferno, etc.) for each encounter. However, there may be a battle that does not need an over-the-top danger, especially the first battle, which I typically use as a warm up. Perhaps I could afford to assign two dynamic features to the final battle. Well, if I can have a steep cliff somewhere else (for PCs to potentially fall off), I can eliminate the option from the final battle. That leaves my finale with the PCs fighting snakemen and a giant snake (which threatens to swallow them) in an underground temple with a collapsing ceiling. Do I like that? Yes! I do.

Step 11. Develop the Sentence

We now have the vision of a final battle scene, but we also have a dozen questions. How did the PCs get to that underground temple? Why did they go to the temple? Since this is a collection adventure (for the sunsword), how did that item get in the temple? Did the PCs know that the snakemen were there? Why are the snakemen in the temple? Is this a new temple or an ancient one? Where is this temple located?

There is no correct way to answer all these, and whatever your method, it will take some time. Do not be deterred. I find that it helps to have a guiding sentence that drives the whole adventure. Good campaigns certainly have these, but I think adventures can too.

To develop the sentence, start with the universal template of ‘someone wants something badly and is having trouble getting it’. I’ll admit I always envisioned the PCs as the ones that badly want something. It makes sense, for they are the protagonists of the story (and the adventure). Yet, Guy Sclanders suggests a different approach that seems to work better. He develops his sentence by focusing on the antagonist (the villain). Why? To paraphrase, many PCs do not have clear or interesting goals, whereas most good villains do. In addition, PCs (and players) do not always like DM-imposed plots as much as we hope that they will. When this occurs, they either half-heartedly follow the plot hook or ignore the hook altogether and strike off on their own. PCs tend to enjoy adventures more when they are pursuing their own interests or desires. If you tell a party that the king orders them to kill a monster, they may comply, that is if they like the king, if they think they will get a sufficient reward, or if they find the cause worthy. Alternatively, if you have the same monster destroy half of the PC’s village, kill their friends, and melt some of their magic items, they will hunt the monster to the ends of the earth. With this in mind, we can design an adventure by giving the villain a clear goal and having the PCs somehow get in the villain’s way. The adventure may even begin with the PCs pursuing their own goals (which has nothing to do with the villain or the main plot). Somehow, we’ll arrange to have the PCs collide with the villain’s plans, which is how they’ll learn of a plot hook. If they voluntarily take the bait, then we’ll have happy players, enthusiastically following the course that we suggested. If they don’t take the bait, we’ll simply arrange for a second encounter. PCs are generally formidable, and if they vanquish the villain or his minions once or twice, he will likely begin to pay great attention to them. If we play the villain well and strike the PCs hard, it’ll only be a matter of time before the PCs enthusiastically pursue the villain via one of our plot hooks. The plan usually works. Thus, I want to make our guiding sentence about the antagonist.

In this adventure, we have snakemen and a giant snake in an underground temple, perhaps led by a magic-using snakeman. What do they want, and how will the PCs come to stand in their way? I want to set the temple beneath the haunted ruins of an ancient city. Have the snakemen just uncovered the temple, or have they been worshipping there for years, undisturbed? I don’t want a large temple complex, as this is supposed to be a short adventure. Let’s say that their snake cult, which is spreading across cities to the east, discovered that they once had a temple in the now-ruined, ancient city. Perhaps a year or two ago, they found an entrance and refurbished a few rooms. Most importantly, they found that a giant serpent had made its lair there (which they see as divine intervention). What do they want now? Let’s keep it simple. Every week or so, they feed the snake, which they believe to be a demi-god. Thus, here is our guiding sentence: The snake cultists want to feed their big snake, but they are running short on food. That’s simple enough. A few minor tweaks (naming the snake and specifying the food) yields the following:

Sentence: Snake cultists want to feed the Serpent of Ur-Ammon, which they worship beneath the ruins of an ancient city, but they are running short on human captives.

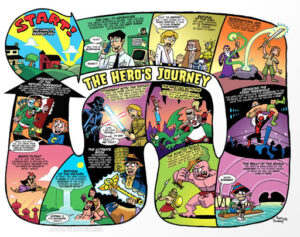

Step 12. Choose a Story Template

At this point, we have a bucket of interesting options, waiting to be used. We also have snakemen looking for more food for their snake-god. We also have the PCs looking to collect a high priestess’ sunsword. Somehow, the PCs’ actions must interfere with the plans of the cultists, giving us conflict and fun.

Before we get into any more detail, we should consider templates. In the past, I seldom used a template. I created locations, NPCs, monsters, treasures, some events that would occur no matter what, and some events that would occur if the PCs triggered them. That was it, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Yet, I want this adventure to unfold more like a classic, epic adventure, even though it’ll be short. Therefore, I will use a template to produce a crude plot outline. I wrote ‘crude’ because it’s important to recall that this plot outline is just a guide.

Sidenote on Using a Plot Outline (feel free to skip):

A good DM must adapt to PC actions as the game progresses. There are purists that believe that certain NPCs and monsters are in specific places on the map, and likewise certain clues to the evil villain’s plans are in certain places, and that’s that. If the players fail to find the clues or unluckily wander into the lairs of the three strongest monsters in your world, then it’s too bad for them. That’s certainly one way to play. With the right crowd, that style can be interesting and fun. Yet, too often, when players hit dead ends, they do not find it fun, and listening to them whine and complain is certainly not fun for a DM. If players are spinning their wheels, I would rather keep the game moving smoothly by slightly shuffling the components in my plot outline. The overall plot, or crude plot, can remain intact, but things may not play out in the exact order that I originally wrote them. I’m fine with that. Remember that the players do not see your outline, so only you’ll know that you made changes.

By the way, this approach does not mean that players will always succeed because the DM will simply shift things to help them. The PCs in my groups have failed on several occasions, and I believe in consequences. The middle path between coddling and ‘survival of the fittest’ lies in keeping the story moving, even if it is not ideal for the PCs. What does this mean in practice? An example may help. In my monthly campaign, an evil cult is doing bad things to inhabitants of the small village of Lakesend. I planned to have the local baron ask the PCs to investigate the disappearance of his provost. A quick investigation (asking around the village) would lead PCs to the realization that several less-important people were also missing. In addition, rumors would point to strangers roaming the village at night and possible kidnappings. Given the two rangers in the party, I figured that they would track the kidnappers or even pose as victims to discover their lair. This would lead them to a sunken manor house, where the cult was converting the prisoners into cultists and then releasing them. In that manor house, the PCs would learn two things: (1) a nearby temple contains dangerous ‘weapons of light’ that can destroy the cult, which is why cultists there chase away the curious, and (2) the cult’s headquarters is in the nearby swamp. Well, the PCs started off well, quickly discovering that others were missing and even that many villagers seemed changed. For various reasons they hit the wall in trying to find the cultists’ lair (part of the fault was mine, for I let them spin their wheels for too long). Eventually, I made some adjustments. I cut out that sunken manor house as a needless complication. Since the PCs are about to finish clearing the abandoned temple, I’ll allow them to learn of the two items above at the temple itself. Thus, the overall plan remains intact (PCs learning X and Y and then progressing toward the cult lair), but the details have changed slightly. There are consequences too. Instead of the PCs receiving the baron’s praise for swiftly unmasking a hidden threat, their rivals at court humiliated them by pointing out their lack of progress. Interestingly, the nasty exchange in the baron’s court made the perfect segue to a trial by combat that I had planned. That next session turned out to be fantastic. The point is that you need to keep the story moving and to keep it interesting, even if the PCs suffer setbacks. In good stories, heroes always suffer setbacks.

Considering Different Templates

So what type of template is best to guide the story structure? I have no answer here. I know of three kinds that all do the same basic thing. There are nuances, of course. The first and simplest is the Five Room Dungeon, which I first heard from Johnn Four, who runs Roleplaying Tips. I have summarized his idea in a previous article. While I find this very useful for tiny adventures of just a few encounters, I’m not sure how it would work with larger ones. I know that John asserts that you can expand it to have 5RDs inside of 5RDs. I think this could ensure that your game contains a good balance of encounter types (role-playing and puzzles/riddles versus combat), as well as a mix of small and large encounters. It would even ensure that you give rewards with some regularity. Yet, I am not sure if it would help to create the flow of a classic story, which is what I’m after here.

Guy Sclanders describes the other two that I know, calling them the 121/122 Template and the Five-Step Template. Online, you can find several of his videos explaining these in detail. In short, the 121/122 is his version of a Three-Act Structure, which provides a beginning, a larger middle, and an end. Yet, it seems to require the DM to know what twists and turns to include in each part. In contrast, his Five-Step Template is clearer to me. The step titles explain the general course of the adventure, while each of the five steps contains one social encounter (role-playing, puzzle, riddle, etc.) and one combat encounter (actual combat or challenges like traps and hazards). This mix keeps play from stagnating. Both templates guide the story along a satisfying path.

For this adventure, I’ll adopt the more rigid Five-Step Template. Each step has combat and non-combat, but the order doesn’t matter. Here is a brief outline of the five steps (again Guy’s videos go into more detail):

Step 1. Introduction to Plot

Combat:

Role-Playing, Exploration, Riddle/Puzzle:

Step 2. Journey to Plot

Combat:

Role-Playing, Exploration, Riddle/Puzzle:

Step 3. Discover New Plot

Combat:

Role-Playing, Exploration, Riddle/Puzzle:

Step 4. Journey to New Plot

Combat:

Role-Playing, Exploration, Riddle/Puzzle:

Step 5. Defeat Plot / Get Rewards

Combat:

Role-Playing, Exploration, Riddle/Puzzle:

Step 13. Develop a Plot Outline

At this point, my brainstorming becomes somewhat circular or less structured. I’ll record some thoughts here so you can see the chaos that is normal during this design step (at least for me). Do not be deterred. It really helps me to write down (or type) many of my thoughts. I can always throw out or delete my notes if they stink. Sometimes it helps to jump around, but I try to work backwards. As I find ideas that I like, I’ll fill in the above template on paper or in a separate computer document. What follows in this section is a slightly summarized version of my more useful thoughts as I had them. If you just want a checklist of steps to follow as a guide, you can skip to the next step. Yet, I think this is the most difficult step so perhaps seeing how another DM fights his way through this process may be of value.

We already envisioned our finale, so we can fill in the combat encounter in Step 5. This will be our battle against the snakemen, led by a magic-using snakeman. The giant snake will also be there to try to swallow the PCs. At some point, something will cause the temple roof to start collapsing, bringing down huge chunks of rock (I have no clue what that will be yet, but that’s ok).

We can also fill in the role-playing encounter of Part 5, which occurs after the battle. In this final encounter, the PCs will speak with the priestesses. If the PCs were successful in retrieving the sunsword, the women would reward them, and there may be varying degrees of success and reward. In collection adventures, the return trip could be important, but in this adventure, the climax will be at the temple. Throwing in several other encounters on the way home would be anti-climactic, so we’ll dispense with those. I’ll briefly narrate the journey home and quickly get to the final encounter with the priestesses. Ok, so one-fifth of the outline is done.

Running from Hovitos in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981): An exciting beginning can be unrelated to the main plot

At this point, I’m wondering why the sunsword is in the snake cult’s temple. Hmmm. I already know that snakemen are looking for human captives to feed to their snake. Are they raiding towns and villages? I don’t imagine them to be that numerous or strong. Perhaps they are simply ambushing travelers. I also know that the PCs will be trying to retrieve the sunsword for the priestesses of Palladine Mithrallas. Let’s start very simply and make these two ideas collide. What if the sunsword is missing because the snakemen, looking for captives, ambushed the high-priestess and her retinue, taking them back to their underground temple? For the PCs to get involved (assuming that they weren’t with the high-priestess), someone has to bring word of what happened. Perhaps a maimed survivor escaped to tell the tale. The priestesses could then commission the PCs to get the sword for them. The PCs could journey to the temple, find their way in, kill the snakemen and their giant serpent, and retrieve the sunsword. Ok. That’s simple and logical. It’s also boring, but it’s a start.

I’m unsure what to do next, so let’s jump to the beginning. I like to start adventures with combat, preferably in media res (meaning in the middle of things, possibly action). It’s fun to sit down at the table, ask if the players are ready to start the adventure, and then say, “Roll initiative.” Borrowing from many Hollywood movies, I often have this first combat unrelated to the rest of the adventure. It gives the players the sense that their PCs are busy doing other things when they are not on one of my crazy adventures. This also allows you to feature a monster that has no relation to your villain or current plot, giving you more variety. The 1981 movie Raiders of the Lost Ark provides a simple and well-known example, with Indy facing half-naked South American tribesmen in the initial encounter, while most of the film has him battling Nazi soldiers and their minions. Well, looking at my list of monsters, I see human brigands and guards. They seem to be the most mundane, so why not start with them? Back in Step 3, I pondered an encounter with the PCs escorting a merchant caravan. Let’s develop that. Looking at my list of locations, I’ll pick the rocky plains. I imagine that the merchants, guards, and brigands will all have horses, so the plains will fit well here. This may yield a fast-moving battle with lots of movement, arrow fire, and weak opponents. In my earlier musing, I had the guard captain betraying the merchants and siding with the brigands (corruption theme), leaving the PCs to fight them all. Perhaps this battle does not need a life threatening dynamic from our list of potential PC deaths. Alternatively, the caravan route could run alongside some steep cliffs. In any case, perhaps sometime after the battle, the lone priestess that survived the snakeman ambush stumbles upon the merchant caravan, which is how the PCs learn of her plight. I like this better than having the PCs make it back to the city before the priestesses ask for their help. Ok. Now our adventure contains an opening battle, a role-playing encounter with the maimed priestess, a journey to the temple, and a final battle (40% done). It’s getting better, but we’re far from done.

The next part that I want to tackle is the ‘new plot’, indicated by the template. In many classic stories, the heroes discover a plot hook near the beginning of the story. They then begin to tackle that plot, whatever it may be. However, sometime afterwards, the heroes usually hit a wrinkle by discovering a new plot. For example, a detective trying to solve a murder (initial plot) might find that terrorists commited the murder to distract the police while they blow up the entire city. The new plot would be stopping the terrorists. Alternatively, heroes that are trying to rescue a princess might discover that her father-in-law is behind her kidnapping for political reasons. The new plot would be to unmask the father’s treachery. You get the idea. The new plot must be significant enough that the heroes can not simply walk away. To use the original Star Wars film as a classic example, the initial plot for Luke was to bring the droids to Alderaan, but he later finds the planet destroyed. After being sucked into the Death Star, the heroes must find a way to disable the tractor beam to allow for their escape. Yet, they also discover that the Princess is there, so they set out to free her. This is the new plot. So far, my adventure is missing a new plot. Since I want my snakemen to be the finale, I need some other people, not the snakemen, to ambush the priestesses. Later, as the PCs try to locate and to retrieve the sunsword (or perhaps to rescue surviving priestesses), they can somehow stumble upon the snakemen’s trail. I played with a few ideas here, but I’m still having difficulty.

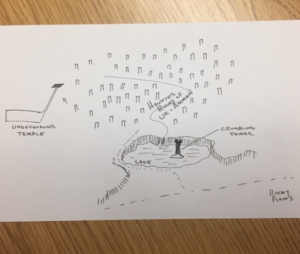

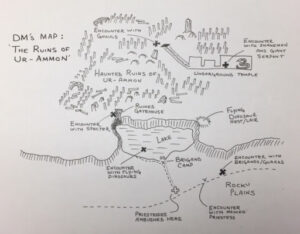

Nothing Fancy: My crude sketch map of five locations

I’m a very visual person, so to help myself, I just drew the roughest sketch map, including my five locations. I have no set plan, save that I want the road through the rocky plains to be where the PCs start and an underground temple to be on the far side of the map, where the PCs will finish. I also took a few tiny bits of paper and wrote one of my five monsters on each one. I’m now moving the chits around to different locations to see if I can make sense of why the PCs might proceed from one location to the next. After some thought, I’ve come up with a few scenarios that make sense and use three or four of the options. Here is one example: The PCs start the adventure with a battle against brigands. Soon afterwards, they meet the maimed priestess, who tells how she and her fellow priestesses were ambushed by brigands ahead (not snakemen), perhaps a few days ago. The PCs follow the brigands’ trail and come to a lake. They find a recently abandoned brigand camp by the lake. There are signs of battle there, but no corpses, for the snakemen have ambushed the brigands and carried them off, along with the priestesses (looking to feed their snake). The PCs can then track the snakemen up to the ruins on the cliffs above, where they would meet ghouls (ruins seem like a fitting place for ghouls). Finally, the PCs find the entrance to the temple, enter, and defeat the snakemen. That’s not bad! It’s shaping up, but I missed the specter, crumbling tower, island, and flying dinosaurs. If this happens, don’t give up. Keep at it.

To be frank, the island with the tower is giving me fits. The PCs have no reason to venture there if a clear trail or path leads right into the ruins (as the sketch here shows). I toyed with different ideas about what might be in that tower. Perhaps it contains the location to the hidden temple entrance. Perhaps it contains a secret about the haunted ruins. Perhaps it has a secret to bypassing the ghouls. Everything comes up short upon close inspection.

After much thought, I now wonder whether the island location could instead be the lake itself. After all, my initial intention had been to set up the PCs for a battle while on a boat. The PCs don’t actually need to set foot on an island to get this experience. They just need a reason to be on a boat on this lake (Alas, I don’t have that reason yet). Perhaps the flying dinosaurs might work well here too. Perhaps they have a perch on the cliffs overlooking the lake, and perhaps they swoop down to attack living creatures. This would give the PCs a battle on a boat against flying creatures. That’s dangerous and exciting. I like that, but I don’t have a reason for them to be on a boat in the first place–not as long as that path runs conveniently up the slopes to the cliffs above. Hmmm. Somehow, that lake needs to obstruct the path. How would this come to be? Well, what if the rocky earthen ramp, which once ran along the edge of the lake and rose to the cliffs above, crumbled many centuries ago? Perhaps an earthquake caused a collapse or erosion wore down the edge. In any case, perhaps the PCs will now come to the lake shore and find a dead end nearby. Perhaps they will be able to spot, on the far side of the lake, the old path continuing up to the cliffs. They would have to cross the lake to continue tracking the priestesses and their captors (or go far out of their way). Of course, players are always apt to derail our best laid plans, so I need a way to discourage them from taking the very long way around. Well, if the PCs are looking to rescue captives, time might be crucial. Perhaps the sunsword, while important, can be secondary. Ok. We’ll change things so that the PCs are initially trying to save the captive priestesses. Yes, I think that will work.

My last lake-related problem is the lack of a way across. Where would they get a boat? I want the city to have been dead for more than a thousand years, so no ancient boats would remain. Then again, the brigands may have had a boat or two at their camp for whatever reason. That makes sense.

Well, in the last few paragraphs, we incorporated the lake (instead of an island) and the flying dinosaurs. We’re now just missing the tower and the specter.

Regarding our last two missing pieces, several crappy ideas have come and gone, but I just realized that I have been operating on an early assumption (that the tower was on an island in the lake). What if I move the tower? I still have no idea what’s in it or why PCs would need to go there, but I could move it. It seems like it would go well inside the haunted ruins of the ancient city, especially if there may be a specter within. That makes sense. Yet, that would put my ghouls and specter in very close proximity. That may be ok. Maybe they are working together. Yet, that seems to reduce the combat encounters from five to four. I could spread them out (the ruins are expansive), but would the PCs run into them both? I guess I could lay the breadcrumb trail right past them both. I have several thoughts, but all are too complex. I want this to be simple. I just had an idea. If I want to make it seem necessary to go into the tower, why not change it slightly into a gatehouse? Perhaps that gatehouse sits on the edge of the cliffs, overlooking the lake. Thus, when the PCs get to the brigands’ camp, find it empty, and find the path ending, perhaps the first thing that they notice is the ruined gatehouse on the bluffs across the lake. Then they can notice that the path continues on the other side, rising up toward the gatehouse. Once they get up there, they must pass through the gatehouse to enter the ruins. That works, but what of the specter? Perhaps it is a spirit from the ancient city. I could come up with a dozen reasons for its existence, but I think that monsters are creepier when you don’t know much about them or how they think. Who knows why it haunts that place? It really doesn’t matter. Ok, I think we’re done stringing together the basic plot (wow, that was a lot of work).

Before we plug items into the template, let’s see if the basic plot sequence makes sense. Our crude outline suggests a story that could unfold as follows:

(1) Combat: PCs start with a fast-paced, outdoor battle (maybe on horseback) against brigands and traitorous caravan guards. This occurs along the edge of a deep ravine, so combatants risk falling 1000’ to their deaths.

(2) Non-Combat: Not long afterwards, the PCs meet a maimed priestess that tells of how her sisters were ambushed and were taken captive by brigands. What if they don’t offer/agree to rescue them? Perhaps the ambush site is still ahead so the same brigands could attack the PCs directly. That would probably do it.

(3) Non-Combat: The PCs find the ambush site (but no bodies) and follow tracks to the edge of a lake, where they find a brigand camp. Strangely, it’s empty. Signs of battle are there, but no bodies. Tracks lead to the lake’s shore. The ancient path that leads along the edge of the lake ends abruptly. The PCs spot a ruined gatehouse on the cliffs on the far side of the lake. They find a boat or two at the camp.

(4) Combat: Flying dinosaurs attack the PCs while they are near the lake (preferably in a boat). These could eat the PCs (maybe tearing them apart if not swallowing them). Drowning is also a possibility, if PCs fall into the water. The dinosaurs may also grab PCs and fly away with them, and PCs wriggling free could fall into the lake.

(5) Non-Combat: On the far shore, the PCs ascend the slope and come to the ruined gatehouse. Perhaps the entrance is now completely blocked with tons of rubble.

PCs could scale the wall to climb through an arrow slit or upper window. They may also find a hidden sally port (the snakeman trail leads there) and a narrow, crumbling, spiral stairway (hazard). The stairwell (or any arrow slit or upper window) leads to an upper room.

(6) Combat: A specter of some kind manifests and attacks the PCs for disturbing it. The floor here may be very weak, risking collapse during combat. If the PCs get past the specter, they would find a door leading outside to the ruined city beyond.

(7) Non-Combat: The PCs then enter sprawling ruins. They must track the captives. Though they don’t know it, the tracks will lead to the entrance of the underground temple. Yet, perhaps that entrance is closed somehow, requiring the PCs to figure out how to open it.

(8) Combat: Either before the PCs figure out how to get into the temple or as soon as they figure it out, ghouls appear and attack them amidst the ruins. I cannot yet think of a way to make this battle dynamic. I also worry what would happen if the PCs arrived here during the day. Perhaps I can time their arrival at the camp for twilight, and the need to save the wounded captives should hopefully keep them from passing the night.

(9) Combat: The PCs enter the small, underground, temple complex and come face to face with snakemen and their giant serpent. Perhaps some captives are in the room, forcing the PCs to worry about them while fighting the snakemen. The sunsword could be here too. Something also causes the ceiling to start collapsing during the battle. Hopefully the PCs win.

(10) Non-Combat: The PCs leave the ruins (hopefully with captives and sunsword), recross the lake, get back to the road, and make it back to civilization, where the grateful priestesses reward them.

Well, that took a long time and a lot of effort, but it’s done. We have five non-combat encounters and five combat encounters. The PCs have a logical goal (rescue captives/get sunsword). The antagonists caused this whole plot because they too have a logical goal (feed the giant snake with captives). The story has a creepy twist (brigands are not holding the captives; snakemen are). The snakemen also obtained the captives in a logical way (raiding the brigand camp). I used four of my five options for PC deaths to make three of my combat encounters dynamic (I’m counting a collapsing floor as a cave-in). This last part, how to use your lists of components, deserves additional attention.

Realize that your lists are guides, not handcuffs. This is important. An example may illustrate how this plays out in practice. My initial list of PC deaths from Step 7 includes a conflagration, which sounds exciting. Yet, I could not think of a reasonable way for a fire to start amidst ancient ruins (ghoul combat) or in the crumbling tower (specter combat). I could have been creative to force a round peg into a square hole. For example, the brigands’ boats could contain barrels of oil that could leak out during the battle. Alternatively, there could be some foul oil on the surface of the lake for some unknown reason. I could also give the flying dinosaurs flaming breath. Since the sky’s the limit, the flying dinosaurs could also have the magical power to cause materials to ignite. Since I found many of these ideas to be stretches (except the flaming breath, which I plan to use in another adventure), I opted not to force the fire idea. Sometimes, more is less. Instead, I changed my list, replacing a fire with the obvious risk of drowning. Thus, four of my five battles now have a dynamic feature. As for the ghoul battle, I’ve run out of my initial five options and nothing extravagant comes to mind. Perhaps, the risk of fantastic death is unnecessary here, especially if I give the battlefield terrain some interesting features. Perhaps the ground is very uneven, featuring several trenches, slopes, or pits (three dimensions always make play more interesting). While pits and trenches do not threaten PC death, they should make the battle more than a slugfest.

Updated Sketch Map for ‘The Ruins of Ur-Ammon’

Before moving on to the next step, I started to fill out that template, but in doing so I noticed a problem. After the introduction, the PCs are supposed to ‘journey to plot’ (in this case meaning that they’d look for the brigands). During that phase of the adventure, they are supposed to have combat. I have none. As I currently have it, they reach the empty camp and learn of the new plot (that snakemen took the captives). In short, my encounters, though logical, are not really aligning with the template. The problem here seems to be that the PCs shall discover the new plot too quickly. Hmmm. What if they don’t know exactly what happened at the camp? They could find a trail, but perhaps the ground is too rocky to allow for tell-tale, sidewinding, snake tracks. This makes me wonder how the PCs would follow, but the answer is simple. They could follow a blood trail left by the captives (and the snakemen are making no effort at stealth). So where might the PCs finally learn of the snakemen? Well, part of me would like to keep that secret until the PCs enter the temple, but that doesn’t fit the template either. They need the wrinkle sometime after the combat with the dinosaurs. Aahh. Perhaps it’s inside the ruined gatehouse, in the thick dust of the upper room, that the PCs notice that the blood trail from the captives is accompanied by non-human marks, like that of a large snake. That should work.

Five-Step Template for This Adventure

Step 1. Introduction to Plot

Combat: Brigands/traitorous guards

Extra Threat: ravine (falling)

Non-Combat: Maimed priestess asks for help

Step 2. Journey to Plot

Non-Combat: Discover/search brigand camp

Combat: Flying dinosaurs on/near lake

Extra Threat: drowning/falling into water

Step 3. Discover New Plot

Non-Combat: Gatehouse entry (hazard: stairs/climb)

Combat: Specter

Extra Threat: crumbling floor

Step 4. Journey to New Plot

Non-Combat: Figure out how to enter temple

Combat: Ghouls

Extra Threat: pits, slopes, trenches, etc.

Step 5. Defeat Plot/Get Rewards

Combat: Snakemen/giant snake

Extra Threat: being eaten / collapsing ceiling

Non-Combat: Receive rewards from priestesses

Step 14. Revisit Potential Traps/Hazards

I realize now that I haven’t made use of my traps and hazards from Step 7. I think I’ll insert a few of these wherever they seem to fit.

The water barrier or water filling a room stumped me for a bit. I’m imagining a trap or obstacle so I don’t count the lake here. My problem is that I envision the ruins as rocky and dead. There must be a stream or river that flows down into the lake, but I don’t want it running through the ruins. I want that area to seem dead. The ruins are also high up on cliffs, whereas I imagine water collecting in low spots. The only possibility that makes any sense to me is a low spot inside the temple, which is already underground. In fact, most of the traps make the most sense inside the temple (a wall of fire, pit or braziers filled with hot coals, and the stone wall/door descending). Only the cliffs stand out. I have two thoughts on using those. The essence of their danger is climbing and potentially falling. If the PCs do not find the sally port at the gatehouse (or if they opt against using it), they can climb the side of the gatehouse and try to enter through an arrow slit or window. Also, if PCs opt not to cross the lake for some reason, they may attempt to scale the cliffs to reach the gatehouse. As for the others, when it comes time for temple design, I’ll try to incorporate the water, fire, coals, and stone door. At present, the temple can be as simple or as complex as I want it to be. It may be two or three rooms or it may be ten or twelve. I am very tempted to make it larger, but I remind myself that this is supposed to be a practice run on Roll20. Thus, I may force myself to keep it simple.

Step 15. Plunder PC Backstories

So far, this is a neat little adventure upon which the PCs may stumble. However, they have no real connection to anything. I’ll now look at what I know of the PCs to see if I can personalize the adventure a bit. The ad-hoc nature of our current online campaign will make this rougher than usual. The group has little glue holding it together, and few players fleshed out their characters much. I‘ll work with what little I have.

No one has any particular animosity to snakes, snake cults, or brigands. No one has yet met the priestesses of Palladine Mithrallas. The half-elf in the party may have the most in common with these priestesses of light and truth. It’s a stretch though. The party’s only cleric is a half-orc that worships Kord. I may be able to work with this, for part of the cleric’s backstory is her confusion as to why Kord chose her. I don’t think she’s answered that yet. Perhaps I can give her recurring dreams about smashing the head of a serpent with a club or even crushing its head with her own two hands. If I go with this, I would send the player this tidbit before we start the adventure. This information would mean nothing until the PCs discover that snakemen took the captives. Thereafter, it should give her incentive to continue on. It may even distract her from the immediate goals of saving the captives and retrieving the sunsword, as she is likely to try to kill every snake in the temple. That might be interesting. It may also give the party a reason to fight the snake cult again in the future (I’d like to develop that group more).

One of the PCs specializes in fighting undead, so the ghouls and specter should make him happy. I need to make sure that he cannot turn them or destroy them with ease. He’s using some unfamiliar class variant, so I’ll need to find out exactly what he can do. Likewise, another PC specializes in fighting spell-casters. He too is using some class variant that I’ll need to ask him about (the tendency for every player to use a strange variant class is one reason why I dislike 3.5). In any case, he should appreciate the magic-using snakeman leader.

Well, that’s not much, but the players didn’t give me much backstory to plunder. The cleric’s dreams seem like they have the most potential. I try to avoid dreams, visions, and prophecies these days, as I tend to overuse them. However, these seem fitting for a cleric. They are also subtle, which fits with the sword & sorcery genre. In addition, the cleric has not had much of the limelight in recent adventures. Maybe the player will appreciate the attention.

Step 16. Customize Monsters

I try to avoid stock monsters like the plague. This game is all about exploring the unknown, and few things are as scary as the unknown. Thus, I shall make sure that each monster has some twist to keep the players on their toes. Let’s go through them in turn.

The brigands and traitorous caravan guards may be the most difficult to tweak, for they are just plain humans.

On one hand, I want these to be the most ‘normal’ monsters in the adventure, for they represent the rather ordinary dangers of the PCs’ everyday lives. I shall avoid spells and other supernatural powers here. For an effective tweak, I just need to exceed the players’ expectations. They probably expect several weak brigands of poor skill. For the most part, I want this to be true, but I also need a twist. Perhaps their riding skills will prove to be enough. On light horses, they can move 24”. Perhaps I’ll give some of them a few bonuses that cavaliers normally enjoy. They may attack as one level higher when mounted. They may have a much lower chance of being knocked from the saddle when hit. Perhaps a few also have bows and can loose arrows without much penalty while riding. I’ll be careful not to make them too skilled–just enough to be noticeable and challenging. Of course, my players tend to approach every situation with a ‘scorched earth’ policy. Faced with nimble, mounted brigands, they are apt to circle the wagons, to hunker down, and to shoot the brigands’ horses. I will not allow them this luxury because many of the caravan guards are traitors. The caravan will be strung out in a long line, and calls to circle the wagons will go unanswered (perhaps traitorous guards already killed some of the drovers). If the PCs simply stay put and shoot at the horses, the brigands will go to where they are not and plunder. Also, the brigands could fight fire with fire, shooting the PCs’ horses, thereby stranding them in the middle of a sun-baked, rocky landscape.

As for the flying dinosaurs, the players will not expect them, for we never see these in our games. Yet, these creatures need to be more than flying stat blocks. I’d like to give each an eagle’s ability to swoop down and snatch its prey, lifting it into the sky. The claws would do damage, of course, but the serious risk after being snatched is actually wriggling free and falling. To give the PCs fair warning, I’ll probably try to snatch an NPC first. I also want to make a mechanic by which the PCs might fall into the lake (the PCs may be on a boat). Perhaps if the dinosaur hits its prey, there is a chance of carrying it away. If that fails, it deals claw damage and knocks the prey down as it swoops past. Perhaps I’ll allow a strength check here (or not, as the boat takes away your ability to ground yourself). Perhaps a dexterity check would make more sense. In any case, failure means that the struck PC will fall into the lake. Of course, others can try to rescue the PC from drowning, but they’ll do this in the midst of battle. That should be fun.

For the incorporeal spirit (not necessarily a specter), I need to decide what its touch will do. I loathe the idea of draining levels. The shadow’s strength-draining touch is a nice alternative, but it must be significant to be scary. Yet, if you drain people too low and if restoration takes too long, the party will likely sit around for a while before continuing. This would kill the game’s momentum. Actually, I don’t think this group ever encountered a ghost, which ages its victims ten years per touch. That could be interesting. The effect is permanent and will affect most characters, but not in the short-term. Let’s go with that.

As for ghouls, we need a twist because the players have faced ghouls many times. Temporary paralysis is fun, but it’s not new. It’s also a potential game-changer if unlucky rolls drop several PCs early in the battle. Hmmm. Perhaps I can kill two birds with one stone. What if the ghouls keep their paralyzing touch (lasting 1d4 rounds), but upon paralyzing a victim, a ghoul immediately sits down and tries to start eating that victim? Perhaps he deals 1d4 in damage per round, plus paralysis (again). That adds the fear of being eaten alive (a horrifying twist), but it also prevents ghouls from concentrating their attacks on the few PCs that remain standing. PCs that don’t succumb should have a chance to rescue others.

Yuan-ti hybrid from Monster Manual II (1983)

For the giant serpent, I’ll give it a constrictor’s ability to crush a PC in its tail. I’ll also add a chance for it to swallow creatures that are smaller than a man (the party has two dwarves and a halfling). For the snakemen, I envision hybrid yuan-ti, with a human torso but snake head and tail (as depicted in Monster Manual II). Each can strike with a sword and bite for 1d8 damage. For a reasonable twist, I’ll add some weak venom to the bite. Perhaps the venom deals 1d4 in damage for three rounds (half if the victim saves). Since I shall not give them each spell-like abilities, perhaps each can fight with two swords, getting three attacks in total.

Finally we need to look at the magic-using snakeman. In keeping with the sword & sorcery genre, I don’t want over-the-top evocation magic (fireballs, lightning bolts, etc.), but I should give him something creepy and dangerous. I was tempted to give him paralysis venom, but this is too similar to the touch of the ghouls. I could give him a few standard spells that seem to go with snakes, like charm person and cause fear. Yet, I dislike both of these because they essentially tell players to stop playing their characters as they wish. Then again, those do seem fitting, and I may be able to use them on NPCs, like the captives that the PCs are trying to save. Perhaps a freed captive walks back towards the snakemen just as the PCs are fleeing the chamber. Perhaps two captives run in fear down a dark corridor that leads back into the heart of the temple. Both of these could be fun and memorable scenes. Perhaps I don’t need to make this leader the main threat in our finale. Perhaps he’ll serve only a support role, like most clerics. I want to avoid spells that simply provide a mathematical modifier (bless, bane, etc.), for though they’re helpful to the caster, they have no flavor. Perhaps the snakeman can summon dozens of regular snakes, which emerge from small holes in the stone wall. That would provide flavor, even if it’s just window dressing. This may be enough.

Step 17. Customize Spells

I do like to include at least one custom spell in each adventure that I write. How would the PCs encounter this spell though? Would it be on a magical scroll or would it be something cast against them? I’d rather not leave a scroll lying around as random treasure. The snakeman seems to be the most logical choice for the possessor of a unique spell. Hmmm. I want it to be something memorable. What would creep out PCs and players? What if the snakeman has a spell that transforms a victim into a snake? Then again, I guess that’s just a polymorph other spell (4th-level magic-user spell). Perhaps the snakeman has a variation of this spell. Perhaps it changes part of the victim’s body to become serpentine (1-2 = legs become a snake’s tail, 3-4 = head becomes that of a snake, 5-6 = both head and legs become snake-like). A successful saving throw against polymorph negates the spell. If it takes effect, however, the change is permanent (though dispel magic will negate the effect). If the change occurs, the victim must also make a system shock survival roll to see if he survives. We’ll also add that the change does not immediately change the victim’s personality, but each passing day brings a 10% cumulative chance that he will shift toward chaotic evil and lose his original identity. Now we just need a name for this. How about ‘transformation of Set’? I like it.

Step 18. Customize Magic Items

It’s time to revisit my list of potential magic items. Remember what I wrote about these lists being guides? Well, now that the adventure is taking shape, I don’t find some of my initial magic items suitable. I’ll simply change whatever doesn’t fit.

The powerful Sunsword in Thundarr the Barbarian (1980)